'What Britain calls the Far East is to us the near north'

![]()

As a war time prime minister, Menzies' fundamental approach to Australia's place on the world stage can be summed up in terms of two central principles. In his very first message to the Australian people as prime minister in April 1939 he had contended that ‘what Great Britain calls the Far East is to us the near north' and that ‘in the Pacific Australia must regard herself as a principal providing herself with her own information and maintaining her own diplomatic contacts with foreign powers'.1 At the same time, he continued to assert that ‘the British Empire exercises its greatest influence in the world...when it speaks with one voice' and that Australia should also act always ‘as an integral part of the British Empire'.2 Throughout his two years as wartime leader Menzies sought to maintain both these principles. In terms of Australia's commitment to the Empire his belief that it would be impossible for Australia to be neutral in a British War underpinned his announcement in September 1939 that Australia was at war because the UK was at war. At the same time, in his view, it was up to Australia to decide the extent to which, and the means by which, it would participate in such a British war, and, crucially, the decision as to whether Australian soldiers would fight on foreign soil. Already in December 1939 the Menzies Government had appointed former senior army office and Commonwealth cabinet minister Sir William Glasgow as Australia's first High Commissioner to Canada, with a particular brief to negotiate policy issues concerning the Empire Air training Scheme. Then, taking this one step further forward and in accord with the need for Australia in the Pacific region to ‘regard herself as a principal', the government was responsible for Australia's first independent ambassadorial appointment when Richard Casey presented his credentials as Australian Minister in Washington on 5 March 1940. Later in the same year Sir John Latham, a former federal politician and Chief Justice of the High Court, began a term as Australian Minister to Japan and this appointment was followed by that of lawyer and Commonwealth Grants Commission Chairman Sir Frederic Eggleston as the first Australian minister to China, based in the wartime capital Chungking. Wartime events temporarily aborted the Japanese appointment but the Curtin Government subsequently built on the precedents Menzies had laid down and also commenced a cadetship system for the training of diplomats.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill with Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies and American Ambassador Mr Winant, whom he presented with Degrees of Doctors of Law, Bristol University, 1941.

National Archives of Australia: A5954, 1299/2 Photo 7465

there should be a 'Dominions man' in the Imperial War Cabinet

With specific reference to the conduct of the war one of Menzies' enduring difficulties was in the search for ways and means of having an effective say in the higher direction of the war. This meant involvement in decision-making as to the use of Australian troops in Europe and the Middle East both in strategic terms and in terms of the priority given to the Japanese threat and the need for Britain to ensure the adequacy of the Singapore base both by stationing a battle fleet there and also sending air reinforcements. Through its Washington legation Australia, under Menzies and subsequently for a few months with Fadden and Curtin at the helm, also sought to play an active role (along with Britain, China and the Dutch) in negotiations with Japan. However the central focus of Menzies' own role in the first half of 1941 centred around his visit to Britain between February and June and his view that Australia's influence on the world stage would come primarily through significant personal involvement at the highest level in making strategic war decisions. To this end he urged that there be a ‘Dominions man' in the Imperial War Cabinet 3 but significantly, as he admitted in a telegram to High Commissioner Bruce in August 1941 neither Mackenzie King nor Smuts, the prime ministers of Canada and South Africa respectively, were at all interested in such representation.4 In the same telegram Menzies even canvassed the possibility of resigning as prime minister to go to London and contended that he believed he would be ‘more effective in London than here where at present a hail-fellow-well-met technique is preferred to either information or reason'. Taking this further there are still those who believe that Menzies may have actually envisaged the possibility he might replace Churchill as head of the British Government. Significantly, after Menzies lost office, the Governor-General Lord Gowrie suggested he might be able to find a seat in the British House of Commons but on this and subsequent occasions when the suggestion was made it was vetoed by Churchill himself.5 Other possible appointments for Menzies, including one mooted as a Commissioner-General for the Far East based in Singapore, did not eventuate (and in any case would have been short-lived) but taken together these episodes illustrate Menzies' strong belief that Australia's role on the world stage would centre on its having a substantial role in the making of policy for Britain and for the empire.

Once the Japanese entered the war Menzies presumably would have moved towards establishing close links with the United States as Curtin did, and this would have been, to some extent at least in the short term, at the expense of the British connection. Menzies' subsequent policies as Prime Minister after 1949, and especially the signing of the ANZUS treaty support the view that, despite his strong emotional and practical attachment to Britain and the Empire, he would, like Curtin, have accepted the close US involvement while also, like Curtin, seeking to retain the close British connection. Thus, in Parliament in February 1945 he contended that it was undesirable that nations of the British Empire should attend international conferences ‘without adequate pre-consultation'.6 Nevertheless, it had been Menzies' government which made the first moves towards establishing Australia's own diplomatic corps, with particular emphasis on adequate representation in the Pacific region, and one can argue that any conflict between heart and head over the US connection caused him real problems only during the Suez crisis in 1956.

Prime Minister Robert Menzies being welcomed by New York City Council Chairman Newbold Morris at La Guardia Marine Terminal, New York, 1941.

Left to right: Newbold Morris, Robert Menzies, Richard Casey the Australian Minister at Washington, and Frederick Shedden, Secretary of the Department of Defence and Secretary to the War Cabinet.

National Archives of Australia: A5954, 1299/2 Photo 7423

View home movie footage of Prime Minister Menzies' 1941 wartime tour abroad - at Bristol University with Churchill and British cities in the blitz.

England: [Menzies Wartime Tour], 1941. National Film & Sound Archive: Title No 50675.

Courtesy Heather Henderson

'Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom'

Curtin's wartime position concerning Australia's position on the world stage was for much of the time the result, firstly of the necessity for the American alliance and secondly, the constant need to secure a role for Australia in seeking to modify the effects of ‘The Beat Hitler First Policy' of the Allies.7 In the longer term his government through External Affairs Minister Evatt also sought to play a significant role in the founding of international organisations, and especially the United Nations. At the same time, Curtin gave very specific attention to the longer term future of Australia's relationships with Britain and the Commonwealth.

The dramatic wartime change in attitude of Australian leaders to the British and American connections received their first and most immediate expression in Curtin's famous New Year message published in the Herald (Melbourne) on 27 December 1941:

Without any inhibitions of any kind I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.8

Viewed in retrospect this message is widely regarded as ‘marking the point at which Australia came of age breaking free from the historic bonds of empire'.9 At the time it attracted strong criticism from Churchill and Roosevelt but Curtin hastened to assure his critics that there was no intention of indicating any real break with Britain.10 Similar limitations need to be applied when considering the significance of the legislation piloted through Parliament by Attorney General Evatt during the second half of 1942 and which provided for the ratification of the Statute of Westminster by adopting ‘five sections of the Statute which did not apply automatically to the Commonwealth but required British as well as Australian enactment'.11 At one level, this long delayed legislative response to the British assertion of dominion status in 1931 might be interpreted as the true legal beginning of Australia's status as an independent nation and hence a further significant departure from the British connection. However, even Menzies in his parliamentary speech on the issue, was prepared to concede that the bill did not embody any ‘great issue of Imperial relations' but rather dealt with ‘technical difficulties which the Commonwealth would be all the better to overcome'.12

In 1942 and 1943 Curtin's primary emphasis in the international arena remained the attempt to reverse Australia's increasing exclusion from decision making concerning war strategy with the emphasis still on the war in Europe and MacArthur insisting that Australian troops were not required for the advance against the Japanese in the Pacific. By the beginning of 1944, however, as the war threat eased Curtin focussed increasingly on Australia's future relations within the British Commonwealth. During what has been described as his ‘fourth empire' speech at the ALP Conference in December 1943, and following on from his earlier call for the establishment of a permanent imperial secretariat for the British Empire, he referred to the British Empire as ‘an association of sovereign peoples' to be augmented by ‘a common policy in matters that concern the Empire as a whole'.13 In April 1944 he placed his proposals for the future of the Commonwealth before the Prime Ministers' Conference arguing that he was not contending for ‘a super state...but better machinery for the discharge of the consultations that are inevitable in closer and more frequent collaboration'.14 Little support was forthcoming for his concept and his proposals were ‘quietly pushed aside'.15

Prime Minister Curtin with American General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the South West Pacific Area, 1943.

JCPML. Records of the Curtin Family. PM John Curtin shaking hands with General Douglas MacArthur, Sydney, 8 June 1943. JCPML00376/69

'collective security which can be organized on a world and regional basis'

Earlier, in another move designed to confirm the continuing British connection and arguably to facilitate the dispatch of British troops to the Pacific area after the war, Curtin had agreed to a suggestion from Britain that the Duke of Gloucester be appointed as Australia's next Governor-General. (On this occasion, Curtin's first choice is believed to have been former Prime Minister Scullin.16)

During Curtin's last year as prime minister the major issue concerning Australia's place in the postwar world was the proposal for a new international organisation in lieu of the defunct League of Nations. On 28 February 1945 in his last major speech to Parliament Curtin dealt with the hopes he held for the outcomes of the forthcoming San Francisco Conference and he addressed these same issues three weeks later in a further statement to Parliament. In the course of the earlier speech he argued that the price the world must pay for peace was ‘less nationalism, less selfishness, less race ambition'17 and in the following month in a further short statement he reiterated that Australia's future security rested on the interaction between the government's defence, ‘the degree of Empire cooperation which can be established' and ‘the system of collective security which can be organized on a world and regional basis'.18

On the structure and nature of the United Nations there were differences between Curtin and Menzies. The latter had regained the UAP leadership and become increasingly influential during the 1944 fourteen powers referendum campaign19 and the process of formation of the Parliamentary Liberal Party. During 1944 he had launched three censure motions against the Government and in May 1945 in the course of a fourth no confidence motion he sought to allow Parliament to discuss the issues being debated at the United Nations Conference in San Francisco. In the course of his speech Menzies expressed doubts about the value of having trustee countries report to the United Nations concerning their administration of colonial territories.20 Similarly, he questioned the value of international commitments to the maintenance of full employment contending that essentially the issue would only be successfully addressed as a matter of domestic economic policy. Menzies also hinted that the Curtin Government might see an international agreement as providing a backdoor alternative to achieving greater Commonwealth control over the national economy with powers such as those rejected in the failed 1944 referendum.

Dominion leaders, the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference, London, May 1944. Left to right: standing - General Smuts ( South Africa), Peter Fraser (New Zealand); seated – Mackenzie King ( Canada), Winston Churchill (United Kingdom), John Curtin ( Australia)

JCPML. Records of the Curtin Family. Empire Conference, London, UK 1944. JCPML00376/77

the United Nations and the Bretton Woods Agreement

In terms of Australia's role on the postwar stage the central issue of Menzies' speech concerned Evatt's forthright stand on the issue of the veto power in the Security Council for the great powers. At a preliminary meeting of Commonwealth countries early in April before the San Francisco conference Evatt, apparently acting on his own discretion, had asserted that it would ‘seem reasonable to press for the complete removal of the veto power' while urging that at least its exercise should be limited ‘except in cases of emergency'.21 In Menzies' view, by contrast, without the great powers the organization would achieve nothing. In his words, ‘the simple common sense of the matter is that not one of the great powers of the allied nations will come into this proposal unless it is satisfied with this proposal'. Such an outcome, Menzies contended, would leave the ‘new world league, like the old one...crippled by the absence from it of vital members'.22 Instead, it was his hope that the great powers would stand together after the war and that would provide ‘the greatest guarantee of world peace'.

From Curtin's perspective Australia needed also to be intimately involved in the debate and decision making about ‘the terms on which the global economy would be reconstructed when the war ended'.23 During his prime ministership Australia was deeply involved in discussions concerning the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, culminating in the so called Bretton Woods Agreement. A major concern for Curtin and his government was the push for removal of trade barriers which might leave Australia's industries exposed without adequate tariff protection which in turn would jeopardize the achievement of full employment. To meet this concern the government's advisers devised a strategy of ‘demanding a global commitment to full employment', a strategy can be perceived as essentially self-interested. In this regard, John Edwards has argued that Curtin personally, perhaps because of his Western Australian base, was more prepared to accept a degree of trade liberalization than those more closely linked to Eastern States manufacturing interests.24 Ultimately, Australia did adhere to the Bretton Woods Agreement but not until well into the life of the Chifley Government and, as it eventuated, Australia was able to maintain its tariff protection structure virtually intact for several decades to come.

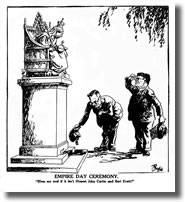

'Empire Day Ceremony. "Bless my soul if it isn't Honest John Curtin and Bert Evatt!"'

Cartoon by Ted Scorfield

The Bulletin, 31 May 1944