The wartime prime ministership of Robert Menzies was bedeviled with party political difficulties

![]()

The wartime prime ministership of Robert Menzies was bedevilled with party political difficulties from the outset. These dated back to events even before he succeeded to the position in April 1939 and his administration came to an end when an internal party revolt forced his resignation. By contrast, Curtin, although he became party leader at a time when his party was deeply divided, was able to nurture party unity before a parliamentary vote made him the last person to date to become Prime Minister of Australia in the wake of a successful no confidence motion in the House of Representatives. Furthermore, within two years he had secured a dominant position electorally and within the party despite strong opposition from at least one powerful press baron. Subsequently, despite the setback of the 1944 referendum, it was only ill health that prevented him from continuing to dominate his political opponents and the electorate until his death in July 1945.

Towards the end of October 1938 Menzies, then Deputy Leader of the United Australia Party, Attorney General and Minister for Industry, had used an address to the Sydney Constitutional Club to call for 'leadership as inspiring as that in dictator countries', an assessment widely interpreted as a thinly veiled attack on his leader, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons.1 The split widened and on 20 March 1939 Menzies resigned from the government after Cabinet agreed to abandon plans for a national insurance scheme, a decision which Menzies described as 'the last but weighty straw'.2 Less than a month later Lyons died and in the situation where the UAP had no deputy leader because of Menzies' resignation the Country Party leader Sir Earle Page was commissioned to fill the post until the successor was elected. It was during this hiatus that Page, seeking to persuade former Prime Minister Stanley Bruce to return to Australian politics as prime minister, made a blistering and widely condemned attack on Menzies which cost him the leadership of his own party. In the upshot, Menzies was elected leader ahead of three other candidates and took office on 26 April, forming a ministry without any Country Party members. Support for Menzies from the press had been strong throughout with the Age on 8 April referring to 'his natural endowments and intellectual attainments' and the Sydney Morning Herald a few days later asserting that leadership would 'stimulate him in performance of the kind Australia most sorely needs'.3

Just over four months after his swearing in, it fell to Menzies to announce Australia's involvement in the war against Germany. Much of the press comment during the months that followed focused on the need for the reformation of the coalition with the Country Party, whose new leader Archie Cameron was said to have a simple political credo: 'there are only two sides to any question - his own and the wrong one'.4 During these first few months the Sydney Morning Herald consistently offered strong support to the government, applauding the establishment of a War Cabinet and claiming that as a consequence of the government's 'intense and soundly directed work...enormous results have been produced in an extremely limited time'.5 Similarly, in its Christmas message the Herald claimed that Menzies 'not only had the capacity to direct affairs in a time of emergency, but also the political skill to hold together a minority government, in the face, frequently of open hostility'.6 Parliamentary opposition to the government was limited during these months though Menzies' announcement at the end of November 1939 that an Australian expeditionary force would be sent to Europe and the Middle East was denounced by Curtin as leaving Australia vulnerable to attack 'should a dire emergency arise during next year'.7 In this regard Curtin had nevertheless to tread a delicate path and for the most part he was constrained from mounting any outright attack on Australia's commitment to the Empire Air Training Scheme or the expeditionary force beyond asserting that Australia's prime commitment must be to the defence of the homeland.

In February 1940 Menzies suffered a serious political setback with the loss of the Corio by-election necessitated by Richard Casey's appointment to the ambassadorial post in Washington. One consequence was that the Country Party agreed to compromise over their demand to select their own Cabinet ministers and a coalition government was formed on 14 March with seven UAP and five Country Party ministers. With the end of the 'Phoney War' in May Menzies, who had, perhaps unwisely, coined the phrase 'business as usual', now had to arouse the nation for an 'all in' war effort. Emergency legislation was passed with Curtin's support, important appointments were made to key wartime posts and Menzies reiterated an earlier offer to take Labor ministers into a national government but this was not taken up.

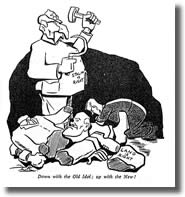

'The Prime Minister has been hinting that he is ready for an election if leaders of the other parties do not stop nagging about his war policy.'

'Archie, will you please stop shoving!'

Cartoon by John Frith

The Bulletin, 8 November 1939

View home movie footage of a parade in Melbourne to welcome Prime Minister Menzies home from his 1941 wartime tour abroad.

From the U.S.A. to Australia: [Menzies Wartime Tour], 1941. National Film & Sound Archive: Title No 50669.

Courtesy Heather Henderson

One issue which caused problems for Curtin was the outlawing of the Communist Party

One issue which caused real problems for Curtin came with the government's decision on 17 June 1940 to outlaw the Communist Party. This decision was made in the wake of the New South Wales ALP State conference which had 'opposed the use of force against any country with which Australia was not at war' for this was technically the situation even though Russia at the time was an ally of Germany. In this regard Curtin had to tread a careful path politically because of ongoing divisions within the New South Wales Labor Party. Although he avoided directly repudiating the New South Wales resolution for the time being, he was not able to stave off a further split in the party's ranks in that state with the Langites forming a separate Non-Communist Australian Labor Party on the eve of the September federal election.8 Nevertheless, following the Corio by-election serious interest had begun to develop in Curtin's potential as a prime minister. The Sunday Telegraph for one, while expressing a number of reservations, was prepared to concede that Curtin had oratorical and conciliation skills which would be a major asset if the opportunity came for him to take power - Curtin was 'capable of ironing out the worst contentions with a masterly summary of conflicting viewpoints, and a motion worded just rightly to resolve them'.9

For several months around the middle of 1940 Curtin cooperated closely with Menzies, claiming that he was more concerned what the enemy would do if additional powers were not voted to government than anything the government might do with those powers.10 While this caused concern and dissension in some sections of the Labor party it made political sense with an election looming. As it eventuated it was Menzies' political problems which mounted in the run up to the September 1940 election, with the government facing a stream of press attacks alleging bungling and inefficiency. On 7 June the Daily Telegraph claimed that the country was 'as unprepared, muddled and confused as Britain was 18 months ago'11 and with problems within the UAP party machine in New South Wales and up to fourteen of his own party said to be hostile towards him, the loss of three Cabinet ministers, all Menzies loyalists, in an air crash at Canberra on 13 August was a major setback. The Sydney Morning Herald on 21 August contended that Menzies, in choosing replacement ministers, needed to 'place national needs ahead of party exigencies'. In response Menzies wrote a bitter three page letter to the editor but this according to his biographer was probably never sent'.12

'Down with the Old Idol; up with the New!'

Cartoon by John Frith

The Bulletin, 27 March 1940

Labor contended that the Menzies Government had conducted the war inefficiently and it fully exploited sectional discontent on issues such as petrol rationing

During the campaign Labor contended that the Menzies Government had conducted the war inefficiently and it fully exploited sectional discontent on issues such as petrol rationing.13 While consistently promising full support for the war effort, Curtin also asserted that the election was about social justice both at the time and into the postwar world. In the upshot the outcome left the ALP with the same number (36) of members as the Coalition (23 UAP and 13 CP), with the latter now dependent on two independents to remain in power. In all, the Coalition lost seven seats (including five in New South Wales) with Labor gaining five and independents two. Curiously, despite all its problems in New South Wales this was the only State where the ALP made significant gains. In Western Australia Curtin himself came perilously close to defeat in Fremantle, eventually surviving by just over 600 votes after a leakage of preferences from an Independent UAP candidate. Certainly, in retrospect, it must be accepted that Menzies' problems with both the UAP and the press in New South Wales had a great deal to do with the eventual demise of his government.14

After the election Curtin once again rejected an offer from Menzies for his party to join a national government. Instead Menzies reluctantly accepted Curtin's proposal for the establishment of an Advisory War Council 'on which Government and Opposition would have equal representation, and which the Government could inform and consult on all matters to do with the conduct of the war'.15 Menzies also reconstructed his ministry with the new Country party leader, Queenslander Arthur Fadden becoming Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer. A few weeks later he and Curtin were able to reach agreement in the Advisory War Council on differences over Fadden's proposed budget after Menzies had been concerned about how far he could rely on some of his own supporters on the issue.16

Before the end of 1940 Menzies had raised both in Cabinet and in the Advisory War Council the idea that he should visit the UK to press for more British reinforcements in the Far East. He left Australia in late January, reaching England at the beginning of the last week in February and he returned in May. During his absence his party political position was being steadily undermined with his opponents in some instances resentful of his 'overbearing manner and sharp wit'17 and also with doubts about Menzies' standing in the electorate and his capacity to pursue his wartime responsibilities. While still overseas Menzies cabled Curtin expressing his appreciation of 'your courtesy and helpfulness' and reiterating an offer of places in a national government.18 By contrast, on his return to Australia and with a by-election in progress in Boothby, a government-held seat in South Australia, Menzies told the waiting pressmen that 'It is a diabolical thing that one should have to come back and play politics, however clean and however friendly at a time like this'. The UAP retained Boothby but daily news of Australian casualties in Greece and Crete and a ministerial reshuffle which left all his main opponents still on the back bench worsened Menzies' position and he was not able to get the States to agree to the imposition of uniform taxation. Against a background of increasing press criticism Menzies managed to survive a hostile party meeting on 28 July. However, when the Labor caucus' refusal to cooperate obliged Menzies to reject an invitation to return to Britain, Menzies found himself deserted by his Cabinet colleagues and he resigned at a party meeting on 28 August with the joint UAP-Country Party members then voting unanimously for Fadden to lead the government. The combination of press and internal party criticism had finally provided irresistible as Menzies conceded in his press statement after the event:

A frank discussion with my colleagues in the Cabinet has shown that, while they have personal good will toward me, many of them feel that I am unpopular with large sections of the Press and the people; that this unpopularity handicaps the effectiveness of the Government ... and that there are divisions of opinion in the Government parties themselves which would or might not exist under another leader.19

Significantly, Arthur Coles, elected in 1940 as independent Member of the House of Representatives for Henty, and who had joined the UAP in June 1941, walked out of the UAP meeting in disgust describing what had occurred as 'unclean' and 'nothing but a public lynching'.20

Menzies remained in the ministry during the short life of the Fadden Government. For a time there was speculation that a place would then be found for him in British politics but this did not eventuate and for many months in Parliament he lapsed 'into comparative silence'21 while still delivering the series of weekly radio broadcasts discussed further below. Even in the uniform taxation debate his main contribution concerned the constitutionality of the measure rather than its inherent principles. However, a few weeks later, and arising out of his key broadcast 'The Forgotten People', he drafted a policy statement for the UAP executive which was formally endorsed in August.

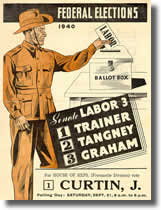

'How to vote' flyer for Labor in WA, federal elections 1940

JCPML. Records of the Australian Labor Party WA Branch. Federal elections 1940, Labor How to Vote pamphlet. JCPML00187/5

Advisory War Council, 1940

Advisory War Council, 1940

JCPML. Records of the Curtin Family. Inaugural meeting of the Advisory War Council, 28 October 1940. JCPML00376/131

'You might need this, Artie'

Cartoon by John Frith

The Bulletin, 3 September 1941

the Sydney Morning Herald suggested that Curtin had become ' a miraculously changed person'

Curtin, for his part, in the immediate aftermath of Menzies' return in May 1941 had to cope both with the increasing pressure for ALP entry into a national government and a spell in hospital with pneumonia. When the request came for Menzies to return to London Curtin, hesitant about taking office with a minority in both houses, was prepared to agree, a move described by David Day as something which would have been 'folly indeed...Fortunately Curtin's view did not hold sway in caucus'.22 When Menzies offered a national government with Curtin as prime minister, the latter refused and instead called on Menzies to return his commission. A few weeks later Caucus decided to test the Fadden Government's support on the issue of the budget and on 7 October Curtin found himself prime minister with his party firmly behind him.

The immediate press reaction to the Curtin government was 'generally supportive' with the Melbourne Age predicting 'ungrudging cooperation' from the community for the government 'in the full expectation, inspired by historical examples, that it will measure up to the tremendous responsibilities of a war for survival'.23 Most of Curtin's potential rivals, other perhaps than Arthur Calwell, were included in the Cabinet while former leader Scullin was to play an important advisory role. When the war situation became critical following the bombing of Pearl Harbour the Sydney Morning Herald suggested that Curtin had become ' a miraculously changed person' and 'the bigger the matter that has come to him, the more decisive has been his handling of it'.24 The paper was less enthusiastic about his New Year's message in the Melbourne Herald expressing concern about 'reflections [on the British] bound to give offence ... to great numbers of people here and elsewhere' but it still conceded that the statement was 'not without value'.25 In May 1942 the same paper reported, following Curtin's parliamentary speech on the battle of the Coral Sea, that everyone in the audience emerged that afternoon 'a better Australian'.26 In general, during the critical year of 1942, Curtin had few if any problems with either the press or his own party - even the move to uniform taxation aroused criticism mainly from State Premiers - until the conscription issue came to a head late in the year.

At a Labor Conference in November 1942 Curtin raised the issue of conscription in connection with the militia (CMF) who, as matters stood, could not have joined soldiers from the AIF in pursuing the Japanese into Dutch New Guinea nor in the East Indies nor could they have been sent to the Philippines. David Day has described Curtin's handling of the conscription issue as demonstrating 'canny political footwork' and in a wider sense his hold 'over the party and the people'.27 Calwell was especially prominent among those who opposed Curtin and even succeeded in having the matter referred back to the ALP State Executives but Curtin carried the day at a special conference in January 1943. Significantly, the bill which eventually went through Parliament strictly limited the territory to which the conscripts could be sent - insufficiently far northwards to include Singapore or eastwards to include new Zealand. In Menzies' view the bill was not worth 'the toot of a tin whistle'.28

The episode was also important in highlighting divisions within the UAP. Menzies and two of his colleagues went back on a party agreement and attempted to amend Curtin's legislation, a move for which Menzies received support from sections of the press including the Murdoch press. Party leader Hughes called a meeting at which attempts to produce a spill were unsuccessful but on 31 March Menzies and a number of supporters formed a breakaway National Service Group (NSG) with the purpose of 'gingering up the opposition'.29 Press reaction was muted, with Murdoch suggesting that Menzies' need to revive his law career might well 'preclude constant touch with the Canberra lobbies'.30 In fact, from this point on Menzies became increasingly aggressive in seeking to regain party leadership - Hughes referred to the NSG as a 'Group of Wreckers' - particularly in the wake of the party's overwhelming defeat in the August 1943 election.

Labor in office: Dr Evatt (Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs) speaking in Parliament. Seated next to Evatt is Prime Minister John Curtin.

Labor in office: Dr Evatt (Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs) speaking in Parliament. Seated next to Evatt is Prime Minister John Curtin.

JCPML. Records of Robert Menzies. Dr H V Evatt speaking in Parliament, 1944. JCPML00544/9.

Original held by National Library of Australia MS 4936 Series 31 folder 15.

in seeking to explain the Labor landslide, Menzies referred to 'the Curtin halo'

Curtin had called the 1943 election in the wake of controversy over Eddie Ward's Brisbane Line and in the midst of press criticism for refusing to take a stronger stand against Ward. During the election campaign proper Menzies clashed openly with Opposition leader Fadden when he publicly repudiated a key plank in Fadden's platform. On the other hand, Menzies followed Fadden in attacking the activities of the Communist Party in Australia, notwithstanding the Soviet's role in the war, and in this regard he received strong support from press baron Keith Murdoch who described Menzies as 'a distinguished man' and on occasions 'the best exponent of the thoughts of all'.31 Subsequently, in seeking to explain the Labor landslide, Menzies referred to 'the Curtin halo' which he described as having been developed by Curtin's skilful press secretary Don Rogers.

The attitude of Keith Murdoch is of particular interest. Murdoch himself over the years had written several critical articles concerning Curtin and these became more frequent during and after Curtin's successful moves to have the ALP accept a limited measure of military conscription beyond Australian territory. In an article under his own name Murdoch wrote that Mr Curtin's Citizen Military Forces could now 'chase the Japs away . . . right to the O in Borneo or to the J in Java'.32 In the same period he wrote that 'the best service to Australia would be for the country thoroughly to defeat the existing government'. In May he attacked Curtin for not allowing the returning Australian troops in 1942 to be diverted to Burma for 'great offensives'. On the eve of the election he suggested that Curtin's was 'an isolationist mind which has expressed itself even in pacifism moves under stress of attack to defence-mindeness' and to 'parochial isolationisms'.33

By contrast, in the wake of Labor's stunning victory, Murdoch was prepared to concede that

the major element in the campaign was undoubtedly Mr Curtin himself, and once away from parliament, he fought it well. He lifted his own side to a dignified level...He stands for Moderation and Victory and the first thing to do is to support him in both lines.34

Throughout the campaign the Sydney Morning Herald had offered consistent support to ' Australia's leader' and, in the paper's view, 'few Prime Ministers have been more explicitly rewarded by the electorate for national services faithfully and competently rendered'. The voters, it was argued were moved by 'strong approval' of the Government's 'record in the war crisis'.35

Turning to the post election era the experiences of the two men in 1944 and 1945 were to be strikingly different. For Curtin his own standing in the electorate was now assured, and there were suggestions that Curtin might be 'on the road to becoming an imperial statesman'.36 However, party political problems also remained including new difficulties with recalcitrant individuals like Eddie Ward and with Attorney General Evatt's commitment to the fourteen powers referendum proposal which was soundly defeated at a referendum in August 1944. Curtin's visit to the USA and UK took a lot out of him personally and the other Commonwealth leaders were not sympathetic to his moves to establish an ongoing executive structure for the British Commonwealth. He did, however, achieve a measure of success in enabling Australia 'to shift the balance of its war effort to producing food and other supplies, rather than providing personnel for the services'.37 In November 1944 he suffered a heart attack and thereafter much of the remaining months of his life was spent in hospital or at The Lodge with only periodic returns to duty and the parliamentary arena.

Curtin's handling of the press, both on his own account as a former professional journalist and life time member of the AJA and through the services of his press secretary Don Rodgers, was 'an important element of his political success'.38 He showed consummate skill in the secret briefings he gave to a select group of Canberra journalists throughout the war.39 Similarly, his handling of his own political party had been masterful and he left it united and in a powerful position when ten years earlier it had seemed on the verge of destruction. And with the electorate his standing was unsurpassed, based above all on 'his patent integrity and humility'.40

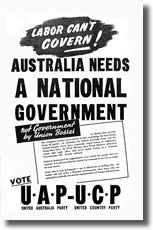

'Labor Can't Govern! Australia needs a National Government' United Australia Party-United Country Party election advertisement, 1943.

The Bulletin, 28 July 1943

View ALP election film footage from 1943 featuring Prime Minister Curtin.

JCPML. Records of the Australian Labor Party WA Branch. Man of the Hour, 1943. JCPML00166/1/1.

Courtesy Australian Labor Party

ss.jpg)

'For effective war effort Vote Labor' Australian Labor Party election advertisement 1943

JCPML. Records of the Australian Labor Party WA Branch. Miscellaneous correspondence ALP State Executive, Federal Elections 1943. JCPML00365/40

Original held by J S Battye Library of West Australian History: MN 300 1719A/17.7

for Menzies 1944 and 1945 form the early stages of a remarkable political renaissance

By contrast with Curtin's decline in health and correspondingly in capacity for political involvement, for Menzies 1944 and 1945 form the early stages of one of the most complete and remarkable political renaissances in Australian political history. Despite Fadden's attempt to attribute the blame for the August 1943 defeat on the National Service Group the pressure within the Opposition developed rapidly for a new party to replace the hopelessly divided and dysfunctional United Australia party and in the interim for a new leader. At the first meeting of Opposition members in the new Parliament on 23 September 1943 Menzies was elected both as Leader of the UAP and of the Opposition as leader of the larger party with a view to then negotiating a coalition of non-Labor forces. Curiously, Hughes at the age of 79 remained as Deputy UAP Leader.

Initially there were teething problems. At the beginning of 1944 Menzies decided to withdraw Opposition representatives from the Advisory War Council, the need for which he had reluctantly accepted after the 1940 election when Curtin refused to join a national government. Menzies felt that by leaving the Council the UAP could 'assist in the essential war and reconstruction effort of Australia best by resuming full freedom to express its views on the floor of parliament'.41 However, the Country party members led by Fadden remained within the Council as did Percy Spender one of Menzies' own colleagues along with Hughes. One of the UAP Senators also resigned from the party criticising the placing of 'party triumph as more important than national welfare'.42

In Parliament the UAP had only 12 members in the House of Representatives and the Country Party 9 but the two parties were not in coalition. There were 49 Labor members and after 1 July 1944 Labor also had a clear majority in the Senate. This seemed to Menzies to leave the way clear for the Government to use its wartime powers to advance socialism as with the establishment of a government-owned aluminium industry or the nationalization of the airline industry. This made it all the more urgent in Menzies' view to achieve the formation of a united and national party to lead the opposition, an objective which he had been pursuing in a series of meetings around the country with various organizations. Significantly, his chances of achieving this objective were given a major boost when the issue of Commonwealth Government power was brought to the attention of the electorate in the so-called Fourteen Powers referendum campaign in July and August.

Prime Minister Curtin, the Governor General (Duke of Gloucester), Arthur Fadden, Billy Hughes and Robert Menzies, Canberra 1945

Prime Minister Curtin, the Governor General (Duke of Gloucester), Arthur Fadden, Billy Hughes and Robert Menzies, Canberra 1945

JCPML. Records of the Curtin Family. John Curtin, Duke of Gloucester, Arthur Fadden, Billy Hughes and Robert Menzies, Canberra 1945. JCPML00381/38

The terms of the referendum, the brainchild of Attorney General Evatt, included seeking the transfer of power to the Commonwealth for five years over a range of issues including prices, the organized marketing of certain products and national health as well as inserting into the Constitution provisions guaranteeing various rights including freedom of speech and religion. Electors were required to vote for the proposed alterations as a whole. Menzies played a prominent part in the 'No' vote campaign which triumphed in four of the six states: only Western Australia and South Australia provided 'Yes' majorities. In this regard it has to be admitted that Curtin personally was distinctly unenthusiastic about the campaign and viewed in hindsight the decision to hold the referendum must be considered a serious political miscalculation. Certainly, for Menzies the result 'seemed to promise a clear turning point in the fortunes of the parties on Menzies' side of politics'.43

In the aftermath of the referendum a circular over Menzies' signature convened a conference of interested organizations and individuals to be held in Canberra in mid October to form a single nationwide party to be known as the Liberal Party of Australia.44 While only one of many working to this end, Menzies was seen by many as the key player prior to and during the October conference. Participants agreed that 'a federal body representing liberal thought be established' with a Federal Council, a permanent secretariat, and with separate State branches each controlling State affairs. The party was to raise and control its own finance and would no longer rely on separate and largely independent fund raising bodies.

At a second conference in Albury in December a draft constitution was prepared and its central policy thrust stated as 'looking primarily to the encouragement of individual initiative and enterprise as the dynamic course of reconstruction and progress'.45 By February 1945 Menzies was able to inform parliament that UAP members in future would be known as Liberals. And there seems little doubt that his standing among New South Wales members was very much on the rise.46

During 1944 Menzies had launched three censure motions against the Government and vigorously opposed legislation setting up a government-owned aluminium industry and seeking to nationalize interstate airlines. By the end of the year Menzies contended that Curtin's ill health was letting 'the wild men' get out of hand.47 During the last months of the Curtin Government, and as the war moved towards inevitable victory for the Allies, he focused on domestic issues, with the fiercest opposition shown to government bills framed to bring the Commonwealth Bank under strong government control and to use it as 'the instrument for guaranteeing financial stability and full employment'. He also sought unsuccessfully with a fourth no-confidence motion in May 1945 to allow Parliament to discuss the issues being debated at the United Nations Conference in San Francisco. Menzies himself described the parliamentary session as especially heavy as the government sought to legislate the various provisions of its postwar plans. In the process he seems to have steadily reduced his already modest level of legal practice.48

Menzies last electoral experience during the war was during the campaign for the by-election in Fremantle, Curtin's seat, for which polling took place just after VJ Day. In the campaign Menzies chose to focus on 'housing, migration, soldiers' rehabilitation and reduced taxation', supporting full employment policies but not 'in a servile State', social services on a contributory basis, the use of secret ballots in trade union affairs and a 'denunciation' of communism.49 Labor retained the seat comfortably and Menzies himself had still to experience another election loss in 1946, one which left him 'devastated' at the time.50 Viewed in hindsight the turning point came with Chifley's decision to legislate to nationalize the private banks setting in train the changing political fortunes which saw Menzies back in the Lodge in December 1949. Perhaps too the Argus in 1943, after Menzies reelection as UAP leader, may have correctly foreseen the importance to Menzies of coming through adversity when it suggested that having, like the Duke of Plaza Toro, led his regiment from behind

not for the reasons which actuated Gilbert's hero, but because of his great gifts...[he n]ow comes into his own on the Opposition side.51

The Sydney Morning Herald came to a similar conclusion:

With all his brilliant gifts, Mr Menzies hitherto has lacked something of the art of managing men...A certain intellectual intolerance has not helped him in the past with his colleagues and supporters of lesser mental stature. Political adversity may have corrected these faults.52

'Churchyard scene from "Omelet"

Alas poor Referendum'

Cartoon by Ted Scorfield

The Bulletin, 26 April 1944