JOHN CURTIN'S LEGACY

John Curtin occupies a unique place among Australian Labor leaders, for he has been elevated by the Party faithful to a place above criticism. When Paul Keating damned Curtin with faint praise, labelling him as 'a trier', Labor supporters were outraged (Jones, 1998). This, and the statements made by various Labor leaders on the subject of Curtin and his contribution to Australia, suggest that Curtin does indeed occupy a special - if not unique - place among Party icons.

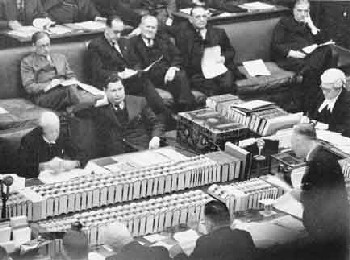

John Curtin (right foreground) addressing the House

during the short lived Fadden Ministry in 1941. Mr Green wears the Clerk's

wig. At rear from left: WM Hughes, PC Spender, AW Fadden, Eric Harrison,

Sir Frederick Stewart, TJ Collins and RG Menzies.

John Curtin Prime

Ministerial Library. Records of the National Library of Australia. Leader

of the Opposition, John Curtin, Parliament House, Canberra, 1941. JCPML00438/12.

Original held by the National Library of Australia. MS3939, series 11,

folder 66

Delivering the John Curtin Memorial Lecture in 1977, Gough Whitlam commenced with a statement that was virtually a call to battle less than two years after the constitutional crisis which resulted in a Labor government being dismissed from office:

So secure is Curtin's place in the history of our country and the affections of the Labor Party that we scarcely feel it necessary to seek new evidence of his greatness or foresight. Yet even the most cursory study of his period in office can yield fresh insights on his life and work. He is, of course, still justly honoured above all as the leader of the Government that in a time of supreme danger ensured the security and survival of Australia. That record, however, should not obscure his illustrious contribution to Australia's peace time development or the lessons it carries for Labor today.

(Whitlam, 1977)

According to Jim Cairns, himself a person of strong principles, Curtin's 'compromises never obscured the force of his ideals ... whenever Curtin compromised it was always a compromise for something'. Tom Uren said that Curtin would be 'my hero until the end of my days' (Uren, 1995). But praise came from the other side of politics, too. According to Arthur Fadden, 'there was no greater figure in Australian public life in my life time than John Curtin' (Uren 1995; Jones, 1998).

These are personal tributes to Curtin, but what of his contribution as prime minister, and his role in making Australia realise its full potential as a federated, autonomous nation? The major areas of his achievement are regarded as being his leadership when placing Australia on a total war footing, and his capacity to push through parliamentary and social reforms during a time of crisis. In regard to the former, Curtin showed an independence previously unheard of in an Australian prime minister. He ensured that Australia made its own declaration of war on Japan, he determined when and where Australian troops would be used in battle, and he negotiated independently with the United States of America (Black, p. xii). When giving the 1977 Curtin Memorial lecture, Gough Whitlam credited Curtin with setting 'the seal on Australia's national unity', because 'establishing and consolidating that unity was the key to his efforts in rallying the nation for war'. Nationalism was a fundamental and pervading element in his character and style of government. According to Whitlam, Australian nationalism was born, not at ANZAC cove, but in 1941 when Australia made an independent declaration of war against Japan.

With

regard to social and parliamentary reform, Curtin inspired guidelines

which are still 'benchmarks' for modern governments: full employment;

uniform taxation; the principal of Federal government responsibility for

education, and a Federal Government role in housing, especially the housing

of low income groups. Whitlam also emphasised Curtin's perception of the

need to reform the Constitution to strengthen Australia's independence.

'[Curtin] knew better than any [other] politician in his day that the

popular aspirations for independence could never be fulfilled while Australia

remained ... a colonial outpost'.

Elsewhere, John Cain has pointed

out that Curtin's Government was 'dominant at the national level like

none before it', yet Tom Uren remarked that:

What mystifies many students of politics, observing the first Curtin Government from October 1941 to August 1943, is that many prominent Labor members - particularly Ward and Calwell - acted as though Labor had a comfortable parliamentary majority when in fact they had to rely on two conservative independents in the lower house and a minority in the Senate. The greatness of Curtin's leadership shone through so clearly (Uren, 1995).

The In passing over the reins to Curtin I did so with the greatest confidence in his leadership abilities, his wisdom and his general capacity … I admired him both as a man and as a statesman.

(Cited in Uren, 1995)

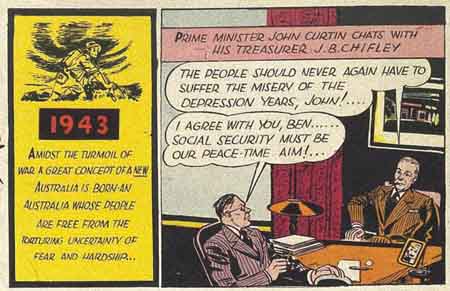

Australian Labor Party election material. '1946 Repeats Itself -Chifley Spells Security'.

JS Battye Library of West Australian History. MN 300, ALP Papers, State Executive Correspondence File 1719A/20/14.

According to John Cain (1996), the real change of direction away from the policies of Curtin's government came - not with the victory and lengthy period in government of the Liberal Country Party coalition from 1949 to 1972 - but with economic rationalist policies being embraced by both sides of politics in the early 1980s. Cain stated:

Much of what was proposed by the Chicago School and others ought to have been seen as a total anathema to a Labor party concerned about social democracy, protecting the under-dog, not to mention fairness and a more egalitarian society. Why would we think free markets would have any morality in allocating resources?

Cain saw the 1990s as being dominated by 'self interest not collective interest'. He observed, 'Australia is heading towards a very different nation from the one John Curtin would have contemplated and ...wished'. He reiterated that fighting inequality was at the very core of Labor's beliefs. 'The principal task of a government is to look after its citizens'. [9] Yet government - the one instrument for collective problem solving - had been 'thoroughly discredited' by the economic policies of the 1990s. Consequently, both Whitlam and Cain saw that within 30 or 40 years of Curtin's death, the style of Federal government for which Curtin had worked was progressively being dismantled and replaced by completely new structures. And, of course, there was the uncomfortable question of 'how far has the ALP moved away from Curtin's ideals?' (Cain, 1996).

While both Whitlam and Cain painted a fairly negative picture of the results of Curtin's legacy by the end of the century, it must be remembered that the context in which he lived and worked has changed vastly in the past 50 years. The technological revolution was largely unknown and unforeseen. The struggles to achieve equal pay and equal opportunity for women and for people of Aboriginal or ethnic background did not feature to any significant degree in Curtin's schema. Racial intolerance, most aggressively exemplified by the 'White Australia' Policy and the laws denying citizenship and self determination to Aboriginal and Islander peoples remained firmly in place for many years after Curtin's death. Curtin was a defender of civil liberties. We may postulate that, had he lived longer or in a later era, he would have pursued these aims with the vigour that he sought to obtain better living and working conditions and improved social services for low wage earners. Similarly, we may postulate, as has Stuart Macintyre, that Curtin would have been a 'mediocre and timid peace-time Prime Minister' (cited in Black, p. xii). But we can never be sure.