NATIONAL LEADER

The Federal elections on 21 September 1940 resulted in a swing to Labor but not sufficient for the Party to take office. Curtin, in fact, almost lost his seat and scraped home by only 600 votes. Two Independent Members held the balance of power in the Lower House. Curtin again refused Menzies' invitation to form a national government but the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party agreed to send representatives to a joint-party Advisory War Council. Menzies was overseas for much of the first half of 1941, and in his absence the UAP experienced bitter faction fighting. Meanwhile, the ALP came to an agreement with Lang Labor which placed the Party in the position to govern.

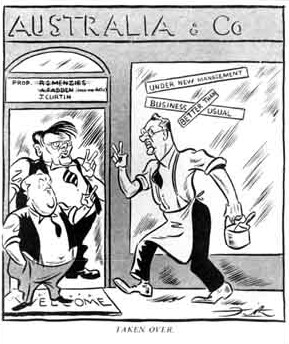

This cartoon expresses the sense of optimism that was felt when John Curtin became Prime Minister in 1941 as a result of the fall of the Fadden government.

John Frith, "Taken Over", 8 October 1941, in The Bulletin p.10.

Courtesy of the University of Western Australia Library

and the Frith family.

In a political crisis in August 1941, Arthur Fadden replaced Menzies as prime minister. Defeated over his budget, Fadden resigned after only 40 days in office, and the Governor-General asked Curtin to form a Labor Government. Curtin became prime minister on 6 October 1941.

At a meeting afterwards, Caucus voted for the 19 proposed Cabinet positions (Weller, vol. 3, p. 294). Curtin published a statement in the Australian Worker, assuring the people that his government would continue to prosecute the war. 'We regard the war as one which affects the basis interests of Labor more than those of any other section of the community' (cited in Black, p. 184).

As prime minister, Curtin worked to implement social welfare legislation to ease the burden of workers and the disparity of the sacrifices imposed by a nation at war. In one of his first speeches in Parliament as prime minister, Curtin stressed his party's commitment to improving conditions for workers and for the poorest sections of society. He announced that his government had raised old age and invalid pensions and had increased soldiers' pay by one shilling a day, six pence of which was sent to dependent wives and parents, and had further increased pay rates for soldiers with children. Curtin said that the government 'endeavoured to improve the capacity of families of soldiers to live reasonably while their husbands and sons are fighting for us overseas' (CPD vol. 169, p. 143).

Curtin also signified that he would work to prevent a repeat of the economic situation of the 1930s by adopting legislation and by maintaining Australia's sovereignty as a nation. Addressing the subject of the Scullin Government and the reasons for its fall in 1932, he described the basic weakness of a system in which the government had no control over funds.

The sympathy which the right honourable Member for Kooyong [Menzies] expressed for my distinguished predecessor [Scullin] would never have been necessary if the Commonwealth Bank in 1931 had done for Labor what it did for our opponents on the outbreak of war in 1939, when central bank credit was used in the national interest by the Government in a perfectly proper manner. I do not condemn what was done in 1939, but I cannot be blamed for drawing attention to the treatment received by [Scullin] who, in worse circumstances, had the door bolted against him while the country was forced through the misery of a depression which might not have been so serious but for the action of those who had no responsibility, and who used their power for their own ends and to defeat the Government.

(CPD, vol. 169, p. 144, emphasis added)

This speech shows that the 1931 experience had left a deep and bitter impression upon Curtin - he took steps to ensure that such a circumstance could not arise again. Perhaps the most interesting feature of this speech is that Curtin regarded economic depression as a worse circumstance than war - or at least than a war which, at that time, was confined to the Northern hemisphere.

Two months after Curtin became prime minister, Japanese forces attacked the US Pacific Naval Base at Pearl Harbour, Hawaii. Curtin was in Melbourne, on the way home for Christmas. Within hours of receiving the news, he made a national broadcast in which he informed the people of Australia that 'we are at war with Japan'. He had already held emergency meetings with the Cabinet, and they agreed to immediately declare war on Finland, Hungary and Romania (Allies of Nazi Germany) and on Japan on 9 December, to coincide with declarations by Britain and the US. (CPD, vol. 169, pp. 1068-9; Black, p. 189). For the first time in its history, Australia had made an independent declaration of war against a hostile power. Curtin immediately explained the commitment that he believed was necessary from the people.

Give of your best in the service of the nation. There is a place and part for all of us. Each must take his or her place in the service of the nation, for the nation itself is in peril. This is our darkest hour. Let that be fully realised ... We shall hold this country, and keep it as a citadel for the British-speaking race, and as a place where civilisation will persist.

(Cited in Black, pp. 189-190)

Curtin expanded the theme of placing the nation on a total war footing in his New Year message, published in the Melbourne Herald. This message contained the famous and much-quoted statement, 'Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom'. But the message contained much more than this apparent switching of allegiances. More importantly, Curtin indicated that Australia would go in an entirely new direction in 1942 because it was on 'a war footing' and because of the foreign policy decisions resulting from his contention that the Japanese war was not a new phase of the European conflict but 'a new war'. Consequently, the United States and Australia 'must have the fullest say' in planning strategy in the Pacific. Curtin's message was praised at home, but criticised in Britain and America (Black, pp. 194-197). In subsequent broadcasts, he took pains to emphasise the 'Britishness' of Australians.

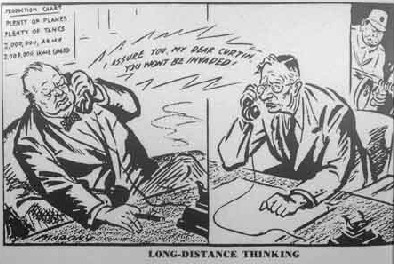

During February 1942, the British Naval Base at Singapore fell and thousands of defence personnel (including the entire 8th Division AIF) were taken prisoner. Japanese planes bombed Darwin, killing 243 citizens. Curtin demanded the right of a voice in defence preparations against the Japanese advance and to determine how and where Australia's defence forces would be deployed. This belief instigated a long and exhausting cable battle with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, firstly over the fortification of Singapore, and then on the deployment of Australian troops returning by sea from the Middle East. Singapore was lost but Curtin succeeded in having the 6th and 7th Divisions AIF returned to defend Australia against Japanese forces in New Guinea and the neighbouring islands.

William Mahony, 'Long distance thinking', Daily Telegraph, 1942.

His decision to place Australia's defence forces at the disposal of General MacArthur as Allied Commander in the South-West Pacific, however, resulted, as military historian Joan Beaumont has observed, in 'Australian strategy was increasingly dictated by the constraints of alliance diplomacy'. Australian forces played a crucial role in the fighting in Papua and New Guinea in 1942 and early 1943. As the Japanese forces were repelled, however, 'Australia found itself progressively consigned to the margins of the main US counter-offensive against the Philippines and Japan'. Australian forces were committed to a series of wasteful and unnecessary campaigns in Borneo, New Britain and New Guinea which had no effect on the outcome of the war (Beaumont, 1998, p. 695).

Apart from defending Australia, the Curtin Government built the legislative framework of Australia's welfare state during 1941-45 (Cain, 1996) and it ratified the Statute of Westminster. The Statute, a 1931 Act of the British Parliament, declared that the self-governing Dominions of the British Empire were fully independent states, free from any British control, and able to form their own defence and foreign policies. Although adopted by South Africa, Canada and the Irish Free State in 1931, the Statute was 'put on hold' by an Australian Government keen to maintain British defence support.

The Statute of Westminster Adoption Act, legislated in October 1942, enabled Curtin to establish Australia's international standing as an independent nation able to deal with other nations through its own diplomatic service. Previously, Australia's diplomatic relations had been conducted throught he British Froeign Office. As well as ratifying the Statute of Westminster, in mid-1942, Curtin's government succeeded in passing four of 'the most far-reaching bills ever debated in Canberra' (Black, p. 211), resulting in the Federal Government assuming control of income tax as a source of revenue. In 1944, the government attempted unsuccessfully to equip the Federal Parliament with the necessary powers for postwar reconstruction and development (Whitlam, 1977; Hirst, p. 609)

But Curtin had to face challenges from within his own party as well as in the external situation of a world at war. The greatest challenge - and the action that generated the most criticism of Curtin as betraying his revolutionary roots - was the matter of conscription for military service. The ALP had always held the position that conscripted service personnel should not be forced to fight except on Australian soil in defence of their homeland. Curtin, however, was uncomfortable with the fact that Australia had two armies: the AIF, recruited to fight overseas and composed entirely of volunteers, and the partly-conscripted Australian Military Force (the 'militia'). He knew that American conscripts were dying while fighting in Australia's defence, and he felt that Australia's insistence on retaining conscripts at home was untenable (Ross, p. 300). Curtin introduced the issue of conscription for overseas military service at a Special Conference of the ALP in Melbourne in November 1942, without undertaking any prior lobbying. Fearing the prospect of splitting the Party, he followed the correct ALP policy procedure by seeking a ruling on the issue by the Party's decision making body before introducing legislation in parliament. The proposal was sent to each of the State Executives for consideration and most voted in support. It was passed at a Special Conference in January 1943 (Ross, pp. 301-305). Curtin then introduced in Parliament the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Bill under which members of the militia (including conscripts) could be required to serve in any area of General MacArthur's command in the South West Pacific Zone. The Opposition had long been calling for the removal of any territorial limitations for the militia. When Curtin finally yielded to the extent of requiring the militia to serve in the South-West Pacific, he was criticised from both sides of the House. Curtin justified his timing of the Militia Bill by saying that his government's policy had not 'impaired the efficient use of the [fighting forces] by the Commander in Chief [MacArthur]' (CPD, vol. 173, p. 26 ff). But the UAP members said that it was too little, too late.

Among Labor ranks, Arthur Calwell, Don Cameron, Eddie Ward and Maurice Blackburn were strongly opposed to conscription for overseas service (Black, pp. 214-216). In a Caucus meeting on 24 March, Calwell accused Curtin of being a turncoat and said that he would 'finish up to the other side leading a Nationalist Government' (Weller, vol. 3, pp. 312-313) Curtin threatened to resign and Calwell was forced to apologise. Curtin's old friend, H.E. Boote, launched a savage attack against Curtin on the front page of the Australian Worker. This must have been particularly hard for Curtin to bear, as Boote was one of a select group of friends that he had maintained since his youth. He depended on these friends to reassure him that 'his present role was in accord with his earlier international socialist beliefs' (Day, p. 458).

Yet, in the midst of these stresses, Curtin maintained his vision of a post-war society. He directed the Attorney General, H.V. Evatt, to explore the possibility of expanding the government's powers to enable planning for post-war reconstruction. In November 1942, a Convention of 24 Commonwealth and State representatives met in Canberra. Curtin used the opening address to outline his misgivings about Federalism as it then operated and to foreshadow the direction his government hoped to move in after the war. Although 'in [the] organisation for total war, the constitutional powers of the Commonwealth Parliament' had 'proved adequate', Curtin stated, what would be the position when peace resumed? Australia was pledged to pursue Clause 5 of the Atlantic Charter: 'improved labour standards, economic advancement and social security'. Would the existing Constitution permit the Commonwealth Government to embark on these essential features of post-war reconstruction? Curtin believed that 'clearly it does not', for 'at every turn in the problem of post-war reconstruction we shall be confronted by some constitutional barrier'. He pointed out that it was not merely a matter of seeking additional legal powers for the Commonwealth, but rather of:

...imposing responsibilities upon the Commonwealth Government on the one hand to develop a progressive and comprehensive post-war policy, and of imposing responsibilities on the State legislatures and governments on the other hand to cooperate fully in the administration of a national plan for reconstruction... The primary responsibility for post-war reconstruction rests on the Commonwealth and that Parliament should have the powers necessary for it to face up to that responsibility.

(cited in Black, pp. 218-219)

A Department of Post-war Reconstruction was established at the end of 1942, with Chifley as Minister. Dr Coombs was appointed as Chief Executive Officer (CPD, vol. 173, p. 193).

Some of the State governments, however, failed to pass the draft constitutional amendment legislation agreed to at the 1942 Constitutional Convention. In March 1944, therefore, the Federal Government introduced in Parliament the Constitutional Amendment (Post-War Reconstruction) Bill. A few months later the Australian people rejected the 'Fourteen Powers' referendum, by which the people would ratify the Commonwealth Parliament's ability, for five years after the end of the war, to make laws concerning members of the defence force and their dependants; employment and unemployment; organised marketing of commodities; uniform company legislation; trusts, combines and monopolies; profiteering and prices; production and distribution of goods; control of overseas exchange and investment, and regulation of the raising of money approved by the Australian Loan Council; air transport; uniformity of railway gauges; national works; family allowances, and the Aboriginal people. Only Western and South Australia voted in favour (Janesch and Hughes, 1988, p. 396).

By the beginning of 1943, the Allies were gaining victories against the Japanese forces in the Pacific. In Parliament on 4 March, Curtin read a message from General MacArthur announcing an Allied victory in the battle of the Bismarck Sea. He commented:

We do not know how long the war will last, but because of this [victory] we can be certain that it will not be lost because of any deficiency in our fighting forces, or in the skill with which they are led. Moreover, I do not believe that there is any other factor which will cause our defeat.

(CPD, vol. 173, p. 175)

Labor went to the polls in mid 1943. Curtin's personal popularity was so great that the ALP campaigned with the slogan 'You can't have Curtin if you don't vote Labor'. In his policy speech, Curtin looked forward to the establishment of a 'stable and peaceful commonwealth of all nations ... In banishing want we shall have gone far to free the world from fear ...' (cited in Black, p. 227). The government was rewarded by a landslide victory. In Fremantle, Curtin turned a previous 600-vote margin into a 23,000-vote majority.

From April to June 1944, Curtin visited the US and Britain. The main reason for his trip was the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in London - the first since the beginning of the war. It is perhaps surprising that the man who had once rejected any concept of an Imperial federation and objected to the Prince of Wales being used as a 'missioner for doubtful causes', now put forward the idea of an Empire Council. In an address on 24 April, he said:

I favour a permanent secretariat of the British Commonwealth, composed of men who would specialise in seeing that members of the family are kept informed and the whole business kept regularised. The form of a close collaboration within the British Commonwealth which I favour is an organisation of a kind which the whole world needs. (Cited in Black, pp. 240-241)

I resolved that America should not go to sleep upon its responsibility ... We had been fighting for two years before you started. The struggle for Australia I felt was vital to the global war against the enemy Powers as was the preservation of any other important strategic locations which were being fought for ... I put it to you quite flatly: If Australia had gone you would have had no place open for a base from which to fight the Japanese. (Cited in Black, p. 245)

Curtin attended Parliamentary sessions between February and April - barely two months altogether. The extent of his contribution to debates in that time, when he was battling illness, is phenomenal but the results were not particularly effective. [8] In the Address-in-Reply debate on 28 February, he made the astonishing assertion that 'the war is a sorry state, but no-one in Australia is cold, hungry or thirsty' (CPD vol. 181, p. 171). In a debate on defence the following month (ibid, p. 889), Curtin said that 'the future fate of the world for peace or war' hinged on the success or otherwise of the San Francisco Conference (at which Evatt and Forde were representing Australia). One of his last speeches paid tribute to Franklin Roosevelt who had died the previous week. His last weeks in Parliament were made more difficult by Menzies and the newly formed Liberal Party attacking him for using the war situation as an excuse to 'socialise' Australia. From other sectors came calls to exert greater government control over industry. Curtin claimed that his government 'would not apply socialisation for the sake of applying it' but that he was convinced that postwar prosperity could only be assured by a continuation of wartime controls and government economic activity combined with private enterprise' (Day, p. 561). And, of course, he led a Party that espoused 'the socialisation of industry' as its major objective.

At the end of April, illness forced Curtin to rest at the Lodge. He never returned to Parliament. His health rapidly deteriorated and he died on 5 July 1945. In Parliament colleagues and Opposition Members were generous in their tributes. Western Australian Labor Senator, Dorothy Tangney, the first woman to sit in the Federal Upper House, said that 'John Curtin never forgot a friend ... Every town in Australia is in mourning today'. Acting Prime Minister Frank Forde declared that 'the captain has been struck in sight of the shore'. Menzies said that Curtin 'sought nothing in politics except the good of all others', reflecting the statement that was chosen for the monument that stands on Curtin's grave in Perth's Karrakatta Cemetery:

His

country was his pride,

His brother man, his cause.