.jpg)

.jpg)

Between 1941 and 1945 Australia took the first decisive steps towards a more independent world view, moving away from total reliance on Britain for its foreign policy and defence. After the Pacific war Australians were only too aware of the extent to which their future security would depend on the direction of developments in south-east Asia and of the importance of continuing involvement by Britain and the United States.

Postwar Transition

Politically Australia made a smooth transition into the postwar world in August-September 1945 despite the death of Prime Minister Curtin. The new leader Ben Chifley (1945-49) had been a close associate of Curtin throughout the war and was a key figure in postwar planning while Herbert Evatt remained as Minister for External Affairs.

Despite these continuities the world after 1945 was very different from that which existed in 1939. While ties with Britain and the Commonwealth were not discarded, especially during Menzies' prime ministership (1949-66), the foreign policy realities which had confronted Curtin at the end of 1941 guaranteed that inevitably the United States would become the most significant of Australia's 'great and powerful friends'.

The central problems faced by Curtin during World War Two are essentially the same problems Australians face today:

• the need to resolve Australia's geographic position in Asia in relation to its European demographic makeup; and

• the need for security by a small to middle power.

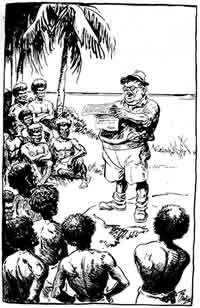

Curtin with Treasurer Ben Chifley,

1940s.

JCPML. Records of the Curtin

family. JCPML00376/132

JCPML. Records of the Curtin family. JCPML00376/170

At the death of Prime Minister John Curtin on 5 July 1945, Ben Chifley became Prime Minister of Australia and led the country into the first postwar years, with Herbert Evatt continuing as Minister for External Affairs.

(200).jpg)