Postwar Policy

By 1945 Australia was attempting to find security and harmony in what was rapidly becoming a very different and more complex postwar world in which wartime developments, such as the ratification of the Statute of Westminster, the development of the United Nations, the signing of Australia’s first treaty and the Bretton Woods Agreement, would play a pivotal role.

THE STATUTE OF WESTMINSTER

The Statute of Westminster, passed through British Parliament in 1931, is a declaration that Australia is an independent state able to form its own foreign policy and defence free from British control. Initially Australia, unlike Canada and South Africa, made no attempt to ratify the five key sections of the Act which required separate Australian action.

The decision of the Curtin Government and External Affairs Minister Evatt in the second half of 1942 to legislate for the parliamentary ratification of the Statute of Westminster was a major step forward in Australia’s preparedness to forge its own legal identity in the international arena.

ANZAC AGREEMENT

The Australia-New Zealand agreement encapsulated the two dominions' concerns about security and status. The agreement was formulated in reaction to a number of important decisions that had been made by larger powers without consultation with either Australia or New Zealand relating to such matters as the future administration and disposal of the Japanese Mandated Territories, the return of Formosa (Taiwan) to China and the future of Korea after the end of the war.

While New Zealand shared Australia's concern at the lack of consultation, Australia took the initiative by arranging for a conference between the two nations to be held in Canberra in January 1944 and then putting forward the suggestion of a treaty.

The proceedings of the conference were considerably expedited by the preparatory work done by the Australian Department of External Affairs and by Minister for External Affairs, H V Evatt. Curtin, who was Minister for Defence as well as Prime Minister, placed the agreement in broad terms when, in a statement to the conference, he indicated that 'security would rest on three safeguards - national defence, Empire cooperation and the system of collective security organised on a world and regional basis'.

The Australian Cabinet ratified the agreement on 24 January 1944 and the New Zealand Government on 1 February.

Although, for the first time ever, Australia had entered into an international agreement to which Britain was not a party, the agreement was generally welcomed by the UK Government and the British press. By contrast the United States' unsympathetic attitude to aspects of Evatt's diplomacy was only exacerbated by this 'regional presumptuousness'.

The Anzac Agreement foreshadowed the fact that Australia, through Evatt, was prepared to put Australian interests forward on postwar settlement issues. The agreement can also be regarded as the forerunner of the ANZUS treaty signed between Australia, New Zealand and the United States in 1951. As Evatt contended in 1944 'it is necessary to get rid once and for all of the idea that Australia's international status is not a reality and that we were to remain adolescent forever'.

(CPD Vol. 179, 19 July 1944, p.229).

UNITED NATIONS

The idea of the United Nations (UN) as an international peace-keeping organization was first spelt out at the Big Three wartime Allied Conference held at Moscow in October 1941. Previously, Churchill and Roosevelt had agreed on a number of broad principles including national self-determination for colonised countries after the war and provision for some sort of permanent security system and these became known as the Atlantic Charter. Australia pledged its support for these principles early in 1942.

By this stage of the war Australian foreign policy was increasingly focussed on dissatisfaction with the Allies' repeated failure to consult with Australia on issues affecting Australia's interests. Both Prime Minister Curtin and Minister for External Affairs Evatt saw part of the solution in improved consultation within the British Commonwealth. This line was pursued, but failed to attract support, when Curtin attended the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in 1944. Evatt came to see that the proposed United Nations organization might give smaller nations, such as Australia, more opportunity to voice their concerns.

The United Nations Conference was held in San Francisco in 1945 and was attended by representatives of 50 nations including Australia. On 26 June the Charter of the United Nations was signed and, following ratification by the five permanent members of the Security Council and a majority of the other signatories, the UN came into existence on 24 October 1945.

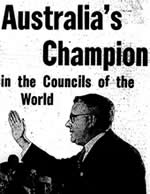

The Australian delegation was led by Evatt and Deputy Prime Minister Forde. At the conference, Evatt displayed enormous physical and mental energy and emerged as a champion of the 'small powers'. According to Evatt the central problem was to ensure that the doctrine of equality was maintained. He argued strongly for adequate representation of small and middle powers on the executive authority to ensure that 'no important group of nations' should be left unrepresented.

Australia proposed 38 amendments of substance and 26 of these were either adopted without significant change or achieved by other means. Furthermore, Australia, through Evatt, was elected to the Executive Committee of 14 which prepared the final draft of the UN Charter. Although the big powers refused to give up their power of veto, Evatt did achieve a decision that the veto could not be imposed when countries were negotiating to resolve disputes. In 1948 Evatt became President of the United Nations, a position of much prestige for Australia.

After Curtin's attempt at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference to improve Empire cooperation failed, Evatt more strongly pursued the United Nations as an organisation that might give smaller nations, such as Australia, an opportunity to voice their concerns |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(150).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)