|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Social Services

The fundamental change between state and Commonwealth financial relations achieved by Curtin through the introduction of uniform taxation in 1942, enabled him to put into place a far-reaching, federally administered range of social services. The financial predominance thus gained by the Commonwealth allowed it to assume leadership in this area and equalise the uneven distribution of social services formerly legislated in a piecemeal fashion by the states.

In 1943 the government made a concerted effort to address a whole range of social issues, putting forward a series of postwar aims for improving living standards, economic conditions and social security by means of the 'National Welfare Fund'. Minister for Post-War Reconstruction, Ben Chifley, wrote a number of articles for the Sydney Morning Herald in December 1943 to explain how the government planned to lay the foundations for a comprehensive scheme, including health services, unemployment and sickness benefits, and family allowances. The scheme was to be financed from consolidated revenue raised through the new uniform income tax, and would comprise £30 million or a sum equal to one quarter of the total collection each year, whichever was the lesser.

The Curtin Government did not expect to be able to introduce all the measures it anticipated would be part of the welfare scheme during the war years. This would allow the National Welfare Fund time to build up a credit balance. According to Chifley: 'the great advantage of the scheme is that the fund accumulates surpluses in good times and distributes purchasing power widely at times when business conditions flag or falter.' (1)

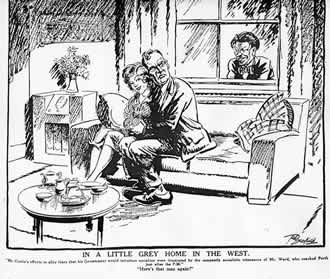

In a little grey home in the West. "Mr.

Curtin's efforts to allay fears that his Government would introduce

socialism were frustrated by the rampantly socialistic utterances

of Mr. Ward, who reached Perth just after the P.M." "Here's that

man again!" Cartoon by Ted Scorfield published in the Bulletin on

12 March 1943.

While Australians were generally in favour of the National Welfare

Fund, they were not so keen on the socialisation of industry or the

banks. In this cartoon, Eddie Ward, a militant Labor MP, peers

through the window as PM Curtin tries to reassure the West

Australian public that he is not planning to introduce

socialism.

Widows' Pensions

The first of the government's social measures was widows' pensions, introduced in 1942, before the announcement of the National Welfare Fund and fulfilling an election promise Curtin had made in his 1940 policy speech. Assistance was granted to widows under three separate categories: widows with dependent children; widows without dependent children but more than 50 years of age; and widows under 50 years of age who were in 'necessitous circumstances'. The Act was generous in allowing for de facto widows, deserted wives, divorced women who had not remarried and women with husbands in insane asylums.

Maternity Allowances

A maternity allowance scheme had been established on a universal basis in 1912 but it was restricted by a means test during the Great Depression, with graded payment depending on the size of the family. In 1943 the Curtin Government introduced changes to the amounts of the payments, removed the means test and provided an additional grant of 25 shillings per week for the four weeks preceding and four weeks following the birth of a child.

Unemployment, Sickness and Special Benefits

Until 1944 unemployment benefits were primarily the responsibility of the states. The Commonwealth Unemployment and Sickness Benefits Act enabled benefits to be paid to men between 16 and 65 and women between 16 and 60 years of age who had been living in Australia for at least 12 months. The benefits were paid as long as the unemployment or sickness lasted and were means tested, but only on income earned. They did not take into account assets such as the family home.

The Special Benefit rates were the same as for unemployment and sickness, but were paid to a person who could not qualify for any such pensions but who 'by reason of age, physical or mental disability or domestic circumstances or any other reason, is unable to earn a sufficient livelihood...' such as a daughter who stayed at home to care for her elderly parents, thus eschewing paid employment.

Age and Invalid Pensions

During the Second World War substantial changes were made to the existing age and invalid pensions, which had been the sole responsibility of the Commonwealth since 1908. The pensions were increased, the qualifying period of residence for age pensions halved and the means test was liberalised.

Housing Assistance

It was estimated that there would be a housing shortage of 250,000 to 300,000 homes by the end of the war. Few new homes were built in the war years because of shortages in material and skilled labour.

As early as 1943 the government set up the Commonwealth Housing Commission to investigate present housing difficulties and plan for the future housing needs of the nation. The Housing Agreement of 1945 included provision for rebates of rent in certain circumstances, with a family on a basic wage paying no more than one fifth its income for rent. The Commonwealth agreed to meet three-fifths of the loss incurred through this arrangement while the states paid for the remaining two-fifths. The Commonwealth's contribution was met from moneys in the National Welfare Fund.

Rehabilitation Services

The Invalid and Old-age Pensions Act provided for the establishment of vocational training for invalid pensioners to help them return to work. In January 1945 the government decided that the Department of Social Services should manage the rehabilitation of disabled ex-service personnel who were otherwise ineligible for benefits.

Health Benefits

Legislation for pharmaceutical, hospital and medical benefits was introduced by the Curtin Government in 1944 and continued by the Chifley Government up to 1949. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Act of 1944 provided for medicines, materials and appliances listed in the Commonwealth Pharmaceutical Formulary to be available free of charge to all residents of Australia. In 1945 Chifley introduced legislation authorising agreements between the Commonwealth and states for the provision of hospital benefits under the Hospital Benefits Act 1945. Although there was extensive opposition from the medical profession which opposed the full operation of such schemes, the foundation of more encompassing health services was laid.

Doubts about the constitutionality of the new Commonwealth legislation were removed through the successful passage of the 1946 referendum which added section 51 (xxiii A) to the Commonwealth Constitution. Under the new provision the Commonwealth Parliament, in addition to existing power to legislate for invalid and old-age pensions, received the permanent power to provide maternity allowances, widows' pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services, benefits to students and family allowances. The substantial achievements of the Curtin and Chifley Governments in the field of social welfare were brought together with the passage of the Social Services Consolidation Act in 1947. (2)

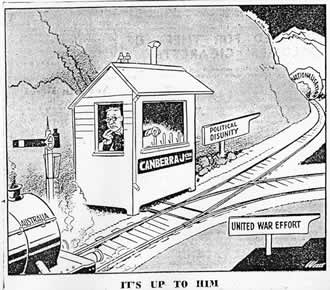

'It's up to him' cartoon by Samuel Garnet Wells

published in the Melbourne Herald on 23 January 1945.

Federal government initiatives in social services won support from

the public but government moves in 1945 to control the aviation

industry raised the fear of socialisation of industry once more. In

this cartoon, signalman Curtin has to choose whether to take

Australia into the dark tunnel of 'Socialisation' or on the clear

track to 'United War Effort'.

Immigration

The issue of immigration has been a thorny one for Australia which has depended on migrants to boost its small population. As a country of only seven million people in the midst of World War Two, the government believed that the nation needed more people to ensure the adequate future defence of the island continent and 'Populate or perish became the government's catch-cry'. (3)

Arthur Calwell became Minister for Immigration in 1945 and was responsible for initiating and promoting a vigorous immigration policy for Australia. Under Curtin's Government Calwell had chaired the Aliens Classification and Advisory Committee between 1942 and 1945 and came to believe that 'most [internees] were excellent citizens' and he 'had few fears about bringing more such people to Australia' after the war. (4) Calwell saw the benefit in widening immigration to include other European peoples and promoted the term 'New Australians'. However, he rejected the idea of allowing Asians to settle in Australia. Like Curtin and others of his generation, he was committed to the white Australia policy. The Australian Labor Party in particular had concerns about migrants competing for jobs with Australians and supported a white Australia policy on the basis that it was essential to protect Australians' high standards of living, fearing that non-European workers would be willing to work for longer hours and less wages than 'white' Australians.

One of Curtin's last editorials for the Westralian Worker in 1928 concerned the issue of the white Australia policy.

[N]o supporter of a White Australia who really understands the policy regards it as hostile to coloured peoples...We believe that the white and coloured races, for biological and economic reasons, are better apart, each in its own country; but we allow that any friendly intercourse for our mutual benefit should not be proscribed but on the contrary should be encouraged. Therefore, we are utterly opposed to the interference by white nations in the internal affairs of Asia, just as we are opposed to coloured immigration to Australia. (5)

Curtin defended Labor's stance on immigration, declaring in 1923 that under Labor in WA immigration was double that under non-Labor governments:

Period of government Immigration to WA

1908-1910 Non-Labor government 21,366

1911-1913 Labor government 50,995

1920-1922 Non-Labor government 22,737 (6)

In his editorial of 1 July 1927 he wrote:

This country could and should afford a welcome and a decent opportunity to every man or woman who, of their volition, seek to come here...He is the kind who, given adequate foreknowledge and placed on an equal footing with the rest of the community from the day of landing in Australia, is prepared to map out his own destiny in his own way. Energetic measures should be taken to encourage that sort of citizen to come to Australia. (7)

The war provided an impetus for immigration not seen before, especially with the promise of full employment as an additional lure for migrants. In promoting immigration, the Curtin Government had to overcome long held opposition and prejudices amongst the populace. According to a 1945 report from the British High Commissioner in Canberra: 'if Australia is to succeed with a migration policy, migrants must be made to feel part of the community' and 'newspapers are again calling attention to the Australian attitude of hostility and suspicion towards persons from other countries...' (8) Similarly the Commonwealth Immigration Advisory Council warned that 'A national publicity campaign should be launched conditioning the Australian citizen for the arrival of migrants, assuring him that the new citizen will make jobs not take them, and educating the public out of its isolationist "attitude" to the new arrivals.' (9)

The Department of Information was responsible in postwar years for promoting Australian trade and tourist possibilities abroad and was instrumental in changing the average Australian's perception of non-British migration during the 1940s and 1950s. In 1947 Australia agreed to accept displaced persons through the International Refugee Organisation. The government paid their passage and they worked for two years in designated jobs. From the end of the war until 1949 more than 500,000 immigrants arrived in Australia to take up jobs in the rapidly expanding areas of manufacturing and construction and in the expectation of having a higher standard of living. The Labor Government set in motion the flourishing immigration intake that followed and that continues to be an important means of maintaining Australia's population.