|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

John Curtin was an avid believer in the right of Australians to determine their own future. As early as the 1920s he was writing editorials about the subject. In March 1923 he wrote:

Australia's status in international politics and diplomacy is a matter which should interest all who have the well-being of this country at heart. Like a plant, Australia is rapidly reaching maturity. Soon it will achieve the dignity of nationhood. Its foreign policy will then be decided by its own Federal Parliament and its ambassadors will be established in the world's capitals. Direct and unrestricted marketing of its goods as a matter of course will follow. National sentiment will be aroused, and pride of country generated. To be an Australian in future will be to declare one's equality in a truly national and international sense. (1)

While Curtin believed strongly in maintaining links with Britain, he did not think Australia needed to be constrained by these ties where it was not in Australia's best interests. In this same editorial of March 1923, he expressed admiration for the 'breakaway progress' South Africa and Canada had made as separate and independent Dominions and abhored the way the United Kingdom exerted economic control over Australia: 'Great Britain has Australia in its financial clutches and the rest of the world is told "hands off".' (2)

In 1937 Curtin was one of the few to question Australia's reliance on the British naval base at Singapore for the defence of the nation:

The Government...declares that the safety of Empire interests in the eastern hemisphere depends upon the presence at Singapore of a fleet adequate to give security to our sea communications. I say to the contrary and to Great Britain that Singapore, having to its position in the Pacific, is more useful as a protection to India against attack by a Pacific power than as a means of security to Australia against attack by a Pacific power...The real purpose and value of Singapore is as protection to India. I now ask how Singapore can be so far away from the Yellow Sea as not to be able to hurt it, and be a thousand miles further away from Sydney and yet be able to protect it?' (3)

Independence from Britain

By early 1942 Australia was facing a crisis after Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, the sinking of the British battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse and the Japanese aerial attacks on Darwin and the north west coast. Curtin wrote his famous New Year's message at the end of 1941: 'Without any inhibitions of any kind I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.' (4) showing that ultimately Curtin considered Australia's interests to be of paramount importance, rather than compliance with British inclinations.

Towards the end of 1942 Curtin and his External Affairs Minister, Dr Evatt, managed to push through the ratification of the Statute of Westminster in order to declare Australia a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire and a fully independent state, free from any British control and able to form its own defence and foreign policies. The Statute was an Act of the British Parliament which had been adopted by South Africa, Canada and the Irish Free State in 1931. In Australia however, it had been 'put on hold' by a United Australia Party Government keen to maintain British defence support.

When the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act was legislated in October 1942 it removed important legal restrictions on Commonwealth powers and this enabled Curtin and Evatt to further develop Australia's international standing as an independent nation capable of dealing with other nations through its own diplomatic service. Until 1939 Australia's diplomatic relations had been channelled almost exclusively through the British Foreign Office, but during the 1940s Australia opened a number of overseas posts.

ANZAC Agreement

It was the impact of war in the Pacific arena and the threat of Japanese aggression which first made it apparent to many Australians that although Australia was close culturally to Britain, geographically it was positioned in the midst of Asia. Curtin had long had an appreciation of Australia's geographic isolation from other countries that shared its European heritage. In 1928 he wrote:

It is true that the civilisation of to-day, or at least the superstructure thereof is mainly European. But civilisation is an unstable and alternating phenomenon and there have been times when the Asiatic has been further advanced than his Western brother. In any case modern communications are so swift and so easy that we must cultivate international co-operation in every way we can or the increased contact will only lead to increased friction, with consequences disastrous to everybody concerned. (5)

While Curtin advocated some form of permanent organisation for the British Commonwealth after the war, Australia's dependence on the United States for security and its wish for America to take a more permanent interest in this part of the world were becoming increasingly apparent. Even within the British Commonwealth, Curtin and Evatt argued that Australia must take responsibility for its own geographical region.

In early 1944 Australia and New Zealand signed a treaty, known as the ANZAC Agreement, asserting that 'a regional zone of defence comprising the South-West and South Pacific areas, and based on Australia and New Zealand, should be established' and that 'the two Governments agree to act together in matters of common concern in the South West and South Pacific areas.' (6) The agreement covered a number of areas including security and defence, civil aviation, migration, dependencies and territories. The ANZAC Agreement was Australia's first international treaty signed independently of Britain and was an attempt by Australia and New Zealand to assert autonomy in their own region.

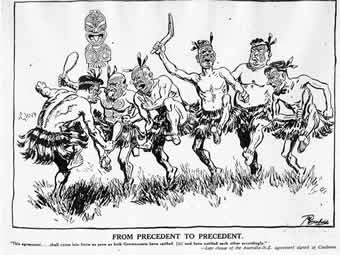

From precedent to precedent. "This agreement... shall come into force as soon as both Governments have ratified [it] and have satisfied each other accordingly." - Last clause of the Australia - N.Z. agreement signed at Canberra. Cartoon by Ted Scorfield published in the Bulletin on 2 February 1944.

United Nations

During the San Francisco conference of April to June 1945 Australia was represented by Deputy Prime Minister Frank Forde and Minister for External Affairs, Herbert Evatt. Evatt became a dominant figure during the conference discussions, working hard to make Australia an active voice for the small powers. According to Evatt, in Australia's view 'the success of the Conference will be measured by one test. Will it bring into existence an organisation which will give to the peoples of the world a reasonable assurance of security from war and reasonable prospect of international action to secure social justice and economic advancement?' (7) While not able to influence the major countries to give up their power of veto, Evatt did have some success in altering the Charter to better reflect the concerns of the smaller powers.

The resulting United Nations Charter was signed by 50 countries at San Francisco on 26 June 1945 and came into force on 24 October 1945, after it had been ratified by a majority of signatory countries and the permanent members of the Security Council. In 1948 Evatt became President of the General Assembly of the United Nations, an appointment which brought much prestige to Australia.

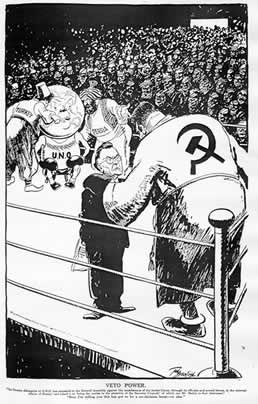

Veto Power. "The Persian delegation to the U.N.O.

has appealed to the General Assembly against 'the interference of

the Soviet Union, through its officials and armed forces, in the

internal affairs of Persia,' and asked it to 'bring the matter to

the attention of the Security Council,' of which our Mr. Makin is

first chairman." "Now I'm telling you this has got to be a

no-decision bout - or else."

In the boxing ring, Turkey and Persia encourage the UN boxer

sitting in his corner, while the Russian fighter with his power of

veto looms menacingly over the Australian referee and tells him how

the fight will end.

Cartoon by Ted Scorfield published in the Bulletin, 23 January

1946.