Labor won a landslide electoral victory in the 1911 State elections with John Scaddan, previously General Secretary of the Australian Labour Federation (ALF), becoming the second Labor Premier of Western Australia. Alex McCallum was asked to take on Scaddan's role at the Trades Hall and he accepted the full time paid position of Secretary to the Metropolitan District Council and the State Executive, resigning as manager of the Government Printing Office to take his first step into a full time political career.

McCallum remained Secretary of the ALF for the next ten years, being re-elected unopposed time after time. In this period he represented WA Labor at numerous interstate conferences and also served for a time as a vice president of the Federal Executive.

Left: Leather wallet and copper plate letter given to Alex McCallum on his resignation from the Government Printing Office, signed by all 99 employees and expressing their gratitude. The letter reads:

'To Alex McCallum Esq,

Dear Sir,

We the undersigned Employees of the Government Printing Office Perth Western Australia beg to ask your acceptance of the accompanying present as a Token of Esteem on the occasion of your severing your connection with the Office in which you have served for many years.

We realize that during your many years service you have always taken a prominent part in everything tending to the welfare of the Office, and every matter having for its object the betterment of the condition of your fellow workers always had your support and assistance, and we take this opportunity of thanking you sincerely for your efforts in this direction.

Trusting you will be long spared to carry out the responsible duties of your office we beg to subscribe ourselves

Yours sincerely , ...

April 1911'

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Memorial presented to Alex McCallum on his resignation from the Government Printing Office, April 1911. JCPML00839/24

Right: Commemorative plaque inscribed 'Presented to A. McCallum by the employees of the Govt. Printing Office, 13 April 1911'

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Commemorative plaque, 1911. JCPML00839/10.

Establishing the Perth Trades Hall - a home for the labour movement

Both Perth and Fremantle Trades and Labor Councils (TLC) had lacked proper meeting places and funds to build them. In 1904 the foundation stone for Fremantle Trades Hall was laid but delays and internal dissension continued to dog plans for a Perth Trades Hall. In its early years the TLC worked under severe financial difficulties and McCallum had to cope with his share of the constraints this imposed.

The Trades and Labor Council was at that time in such a 'flourishing' position that it was seldom able to pay the secretary any salary or rent a place wherein to hold meetings. Mr McCallum mentioned the trying period of industrial work when he had taken over the preparation of the case for the Shop Assistants’ Union. They had often wanted to get into the office of the Council, but could only do so at night, because the bailiff had possession during the day.It was not surprising therefore that when McCallum became General Secretary in 1911, he made a new permanent Perth Trades Hall a first priority. It was mainly through his efforts that the Shearer Memorial Hall site in Beaufort Street, owned and used by the Presbyterian Church as a Sunday school, but well suited as a temporary meeting venue and a permanent site for the Trades Hall, was purchased. He canvassed unions, raising £2 500, and when the Hay Street block owned by the TLC was auctioned, the TLC and the Directors of the proposed Labor Daily newspaper put in a joint offer of £4 000 for the Beaufort Street site. Within six months, work had started on a two story twenty room brick building next to the existing hall which was officially opened as the Perth Trades Hall in 1912 by Premier Scaddan.

'Labor’s tribute: Presentation to Mr A McCallum', Daily News, 10 September 1921 [1]

Left: Prime Minister Andrew Fisher visited Perth in 1911 and laid the foundation stone for the Perth Trades Hall, opened the following year by Premier Scadden.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Prime Minister Andrew Fisher laying the foundation stone for the Perth Trades Hall, 8 August 1911. JCPML00830/178

Right: Perth Trades Hall, a home at last for the labour movement in Perth.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Bobbie Oliver. Perth Trades Hall, n.d. JCPML00568/12

A tireless worker for the Labor cause

Alex McCallum was a member of the 1911 Royal Commission into the Alleged Shortage of Artisans and from 1914, a director of the Westralian Worker, the restructured Labor weekly newspaper, and treasurer of the Workers’ Education Association (WA). Additionally, he tried unsuccessfully to win election to the House of Representatives in 1913 and 1914.

As General Secretary, McCallum organised many groups of previously unorganised workers into unions and provided leadership in numerous industrial battles, laying the foundations of industrial unionism in the west. He was responsible for the drafting and advocacy in the Arbitration Court of scores of industrial awards and agreements. 'Fearless in industrial fights, Mr McCallum was the best-hated man in the Movement by the employing class - but he was also the most feared man.’ [2]

While his influence in the Labor movement was growing, so was the work load that he carried, with seeming limitless energy.

Alex McCallum was in the forefront of the fight for a reduction in working hours. To do so he worked all hours himself. Living in Fremantle, he used to catch the last train from Perth night after night, and when he was not on the train, he was back in the office working. Many nights he slept only for a few hours at his office, but so great was his store of physical and mental energy that he worked the following day with undiminished application.

Those who knew him only by name regarded Alex McCallum as a 'red ragger’ in the days when he was in the forefront of industrial Labour. Such a reputation was ill deserved. He was connected with many industrial disputes - the nature of his job made that inevitable - but he was much keener on settling strikes than in starting them. The strike weapon he rather despised; he preferred the cut and thrust of conciliation. He was never so mentally exhilarated as when the industrial situation facing him was a difficult one, and upon him rested the responsibilities of making the moves.

'McCallum the man', West Australian, 14 July 1937 [3]

Alex McCallum was union representative in 1917 at meetings with employers, employees and educationists on training apprentices, and this provided a sound basis for his later establishment of the Apprenticeship Board in 1926. [4]

From 1918 to 1920, he served on the WA Repatriation Board and his work in this area was acknowledged by the Commonwealth Department of Repatriation, which commended his 'great contribution’ to the 1920 Australian Soldiers Repatriation Act. [5]

Top left: Australian Labor Federation commemorative medallion, inscribed 'ALF 1913 ACM. To Alex McCallum in recognition of a great fight. Federal Election 1913'

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Commemorative medallion, 1913. JCPML00839/22

Top right: Commemorative medallion, inscribed 'For assistance rendered re 8 hours Principle on Railways 1914. Alex McCallum, Federated Amalgamated Govt. Railway& Tramway Service Association of Australasia. One Industry, One Association. NSW, Victoria, Queensland, S. Australia, W. Australia, Tasmania.'

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Commemorative medallion, 1914. JCPML00839/23.

Bottom: Alex McCallum (seated, 2nd from right) with other members of the WA State Repatriation Board, c 1918

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Western Australian State Repatriation Board members, ca 1918. JCPML00830/190

A staunch fighter against conscription for overseas service

Premier Scaddan led Labor to a second electoral victory in 1914 but the conscription issue was to split the Labor movement in the years of the Great War. In 1914, both McCallum and ALF President Doland were strongly against the war, but they were in the minority. Most of those in WA Labor supported Prime Minister Hughes and the war effort. [6]

In 1915, McCallum took on more responsibility when he was appointed as a member of the War Council of WA. [7] His brother Duncan was in France fighting with the Australian Imperial Forces.

Working long hours under constant and heavy pressure took a toll on Alex McCallum's health and in May 1916, in the midst of the war years, he suffered a nervous breakdown. The ALF State Executive unanimously agreed that he should take six months leave on full pay and receive a cash testimonial to enable him to pay expenses of his holiday. It was felt it was 'the least that could be done to repay Mr McCallum for the magnificent services rendered by him to the movement’. [8] McCallum travelled extensively in the eastern states and then through the Northern Pacific group of Islands up to New Guinea. He wrote a long and detailed report on his thoughts and predictions for this country. [9]

When Hughes moved to introduce conscription and a referendum was called on the issue, Labor supporters in WA, as in other States of Australia, held strongly opposing viewpoints. In McCallum’s absence, pro-conscriptionist James Cornell was appointed Acting Secretary of the State Executive and at its triennial conference in June, the WA Labor Party refused to commit itself to oppose conscription.

Still on extended leave, McCallum was in Melbourne and Sydney during the campaign on the conscription referendum. While in Melbourne he visited the famous Yarra Bank on a pleasant Sunday afternoon and listened to the fiery oratory of an up and coming young unionist and journalist called John Curtin, at that time secretary of the National Executive of the Anti-Conscription Campaign in Victoria. In late October 1916, the Australian people voted by a narrow majority against the introduction of conscription but in WA the vote was 70% in favour of conscription.

McCallum traveled on to Adelaide but in response to a telegram from Perth on 6 November, he returned to Melbourne to attend a National Executive meeting and a special Interstate Labor Conference. Following his brief, but not his personal convictions, he voted against the non conscription motion at the December conference. The conference passed a motion to expel all Federal Members of Parliament who had joined the National Labor Party (ie pro-conscriptionists); WA was the only state to vote against the resolution. [10]

The anti-conscriptionists on the WA State Executive, including Alex McCallum now 'wonderfully recovered in health’ [11], worked to remove the influence wielded by the pro-Hughes contingent and the bitter struggle in Labor ranks over the conscription issue continued, with nine State members being expelled in March 1917, including party leader, John Scaddan. [12] The bitterness felt towards McCallum by some within the party over these expulsions was captured in this vitriolic verse published in a 1919 Perth newspaper and kept by McCallum in a leather wallet which also housed a threatening letter and more press clippings, some flattering and others the opposite.

Scad Hun-

’I’m Scad from Albany afar,

When chance goes by I rush it.

I do not drive the Nat’s mo-car,

But run behind and push it.

Mac’s got his knife in me you bet,

Tho’ once we were sworn cobbers,

Because I left his hungry set

And joined up with other jobbers.’All voices-

’Maccallum! Maccallum!

We’d like to overhaul him,

He’d curse the morn that he was born

If we could catch Maccallum.

'MacCallum', by 'Bricktop’, clipping from unidentified paper, 1919 [13]

Left: ' Souvenir from France' sent to Alex and Bessie McCallum from the front line in France by Alex's brother Duncan, 1917

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Post card from Dunk to Alex and Bess, 1 February 1915. JCPML00832/2

Right: Crowds at an anti-conscription rally on the Yarra Bank, Melbourne, 1916. On back of image, John Curtin wrote 'The people’s forum: taken early in the day when the crowd was collecting'.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Tom Fitzgerald. Crowds gathering at Yarra Bank, 21 October 1916. JCPML00687/15/3

Mentor and colleague of John Curtin

Two months earlier, in January 1917, Alex McCallum welcomed John Curtin to Perth as editor of the Westralian Worker. McCallum had recruited Curtin to replace John Hilton, who knowing how divided Labor ranks were, had tried to keep the paper neutral on the conscription issue. By contrast, Curtin adopted a strong anti-Hughes line from the start [14] and McCallum also attacked his former hero in a printed speech, accusing Hughes of dictatorship for defying Caucus and precipitating Labor’s conscription split. [15] Hughes had announced a second referendum would be held on the issue of conscription and in Perth, John Curtin, Alex McCallum and new party leader, Philip Collier, led the anti-conscription campaign. Curtin and McCallum opened the campaign in Fremantle with a Sunday meeting at King’s Theatre on 25 November. At a later meeting on Perth’s Esplanade, with support for their cause growing, Curtin and his fellow speakers found that 'the carrying power’ of their voices was 'taxed to the very utmost’ to reach the huge crowd that was present. [16] McCallum toured the Goldfields in an attempt to unify the movement and 'appease the disaffected’ [17].

In September 1917, Labor, seriously weakened by the conscription split, lost in the state elections and Henry Lefroy was thrust into the premiership, leading a National Government based on a coalition of ALP defectors, led by John Scaddan. McCallum himself was unable to take the Yilgarn seat from a Labor defector. [18]

However in December that year, even more Australians voted against conscription in the second referendum on the issue. Only WA retained a sizeable Yes majority, though less than in the first referendum. The issue was now settled with no further attempts by Hughes to introduce conscription during the remainder of the war.

Alex McCallum and John Curtin became firm friends, working just down the street from each other and spending every Sunday morning in long discussions on the future of the party. For the next eleven years, they maintained a close and ongoing relationship, with Alex being a welcome visitor to the Curtin family home in Cottesloe. [19] Alex McCallum was a key associate of John Curtin, supporting him in his editorship of the Westralian Worker and encouraging his efforts to enter Federal politics. The two men were of like mind on many matters and worked together to advance the Labor cause in WA over two decades. Don McCallum paints a picture of his father as an important mentor and enduring friend of John Curtin.

My father came home one evening and said …’Bess, I can’t do the things for this Party I want to do until I get a Labor Government into Australia. I can’t get Labor in Government until I can get Labor’s Daily Newspapers... I am going to find somewhere a dedicated professional journalist to take charge of it. Even if I write every line of it myself for a few months to teach him what I want.’ My delightful Mother calmed him down and told him she thought he was perfectly correct but doubted if he would find such a person in West Australia.

'All right, I’ll scour the Eastern States, but I intend to find him.’

It was only a few weeks later that he embarked upon his mission. There were no aeroplanes. There was no connection yet made between the railhead at Kalgoorlie and Port Augusta in South Australia - 1,000 miles away. He sailed on the McIlwraith McEachern red and black funnelled Katoomba and searched and searched and searched for the man he wanted.

Eventually he went to the famous Yarra Bank in Melbourne on a placid Sunday afternoon and listened to an amazing oration by an accomplished young Australian journalist. His name was John Curtin. He saw a lot more of John Curtin in the next few weeks, sought out his views, checked his sincerity and other things and offered him the job. Curtin accepted. The rest is history. Wonderful history for Australians and Australia as time was to prove. At last Curtin had found a man who understood him and at last McCallum had found a man who talked his sort of language. They became friends immediately.

Curtin married a very sincere young lady called Elsie Needham. That started not only a happy family life for them at the beach side suburb Cottesloe WA but at last Curtin had been provided with the means to express his views of the sad plight of the under privileged.

The 'Workers’ offices were located in Stirling Street Perth and only a mere stones throw from the Trades Hall in the parallel thoroughfare of Beaufort Street. McCallum and Curtin saw a lot of each other almost every day but there was more to it than that.

Every Sunday morning Curtin would board one of the dreadful old carriages composing part of the funny old train that ran on a 3’ 6” track between Perth and Fremantle. In those days it would take precisely 40 minutes between the City of Perth and the Port of Fremantle - precisely 12 miles away, no less and sometimes more to do the journey. He would disembark at Fremantle and then walk for about 20 minutes to our home located one mile further on.

The discussions that followed were exciting. I was permitted to attend them in my father’s small study - but was enjoined that I must under no circumstances interrupt, nor must I ever disclose any details of the matters discussed. 'I want him to stay in here and listen Jack. I want him to learn all he can about politics and if he doesn’t learn it here with us he will never learn’. Curtin readily understood and then proceeded to listen avidly to all my father had to say. Around about mid-day my father used to say 'Would you bring in a jug of cold water and two glasses Son?’ He himself would produce a bottle of whisky from the cupboard and he would always say 'Well, Good Luck Jack. I will someday make you Prime Minister of Australia’.

He was right, he did precisely that and Curtin later became Prime Minister. But the thing that none of us knew was that he would not live long enough to see the fulfilment of his prediction. Politics exhausted him and every fibre of his body. We were not to know that in those days. The Sunday Morning intensive discussions still went on and always with more and more enthusiasm. [20]

In April 1918, the Governor General convened a conference to obtain support from the labour movement and other representative groups for boosting voluntary recruiting. Alex McCallum travelled with Philip Collier to attend the Melbourne conference as representatives of WA Labor. It took them three and one half days to get there via the new transcontinental railway. The conference supported recruiting but with many conditions imposed by the union delegates.[21]

Labor’s 1918 Federal conference, which saw 32 delegates gathered in Perth in June, also signalled how much the Labor movement’s attitude to the war had changed since 1914 . South Australia and Tasmania, short of funds, sent only three delegates each but Tasmania boosted its representation by accrediting Curtin and McCallum as proxy delegates. After supporting a peace resolution, the conference gave continued support for voluntary recruiting only after animated debate and with a number of provisos. [22]

Top left: Election flyer from Alex McCallum to the Yilgarn seat electorate, 1917.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Letter [flyer] to electors of the Legislative Assembly seat of Yilgarn re state election, 29 September 1917. JCPML00821/25

Top middle: John Curtin (left) with Bessie and Alex McCallum (middle), 1930s

John Curtin, Bessie and Alex. John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. John Curtin, Bessie and Alex McCallum. 193? JCPML00830/25

Top right: Alex McCallum's bound copy of the proceedings of the Governor General's conference on recruiting, 1918.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Report of the proceedings of the conference convened by His Excellency the Governor-General on the subject of the securing of reinforcements under the voluntary system for the Australian Imperial Force now serving abroad, held at Federal Government House, Melbourne, April 1918. Personalised copy - A. McCallum, Esq. JCPML00822/7

Bottom: Both Alex McCallum (back row, far right) and John Curtin (middle row, 5th from right) were delegates at the Interstate Labor Conference held in Perth in June 1918.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Lloyd Ross. John Curtin at Interstate Labor Conference, Perth, 17 June 1918. JCPML00799/3

A skilled negotiator - defusing the 1919 'Battle of the Barricades'

In mid 1917, Prime Minister Hughes formed a number of National unions for the alternative workforce he employed in his disputes with established unions. In Fremantle, Hughes’ National Waterside Workers’ Union (NWWU) was in dispute with the Fremantle Lumpers’ Union (FLU) and strife on the waterfront simmered and flared over the next two years. All of McCallum’s courage and skills in negotiation were needed to defuse one such dispute, the potentially explosive 'Battle of the Barricades’ riot on Fremantle Wharf on 4 May 1919. Hal Colebatch, who had taken over from Lefroy as WA Premier just the previous month, had intervened in the dispute over the unloading of the coastal trading ship SS Dimboola and violence escalated when members of the FLU threw missiles and stones from Fremantle wharf at launches carrying the Premier and labourers who were planning to erect barricades to allow NWWU members to unload the ship. Police retaliated with missiles and bayonets, shots were fired and a tense stand-off with sporadic violence ensued. There was the added danger that soldiers on the troopship Khyber, which had just entered the harbour, might be drawn in to support the FLU.

Alex McCallum was in an emergency meeting with senior police and Fremantle MLA Ben Jones when further shots were heard. He said, 'I must stop this’ and ran to the fence where the numbers of FLU supporters had swelled to 4000. The Riot Act was being read and ammunition issued to police. Acting quickly, McCallum convinced the Premier to leave and gained his assurance that the NWWU workers would depart the wharf immediately. McCallum then convinced the crowd to leave quietly and let the dispute be settled by negotiation. The Lumpers complied and a serious riot was prevented.

Official reports put the injured at 26 police and 7 Lumpers, though witnesses put the number of Lumpers hurt much higher. Seriously injured were Edward Brown, who was bayoneted and William Renton who was bashed in the head by four policemen. Thomas Edwards died as a result of a skull fractured by a police baton. The West Australian's reporter wrote 'One false step on the part of either side would certainly have resulted in numerous deaths and hundreds of casualties.’ [23] Thousands of 'sad and solemn men and women' attended Tom Edwards' funeral the following Friday and the State virtually came to a standstill to observe three minutes silence in his honour. [24]

Don McCallum presents his version of his father’s role in defusing the riot and while the details of the anecdotal memory are not necessarily accurate, the excitement and tension of the scenes at the Wharf are vividly conveyed:

These wharf labourers, (they were called 'lumpers’ in West Australia) demanded that the Premier Sir Hal Colebatch come to Fremantle and discuss the position with them direct.

That was the only way West Australians understood - the direct approach man to man. Colebatch refused. The men then set about it their own way. In the sand hills near Smelters Jetty, south of Fremantle, they made improvised bombs out of condensed milk tins, and in the dark of one night removed the steel spear shaped uprights that surrounded the lovely old Church of England opposite the Fremantle Town Hall. These were dangerous weapons, but the men were ready. Laying at anchor in Gage Road outside of Fremantle Harbour were half a dozen troop ships packed with our wounded plus uninjured 'Diggers’ returning after their triumphs at Paschendalle, Villors, Merettomeaux, Mont St Quentin and other famous battlefields. The wounded needed to be got ashore as quickly as possible, and the remainder were in no mood to be cooped up in troopships any longer. There was their beloved Australia in front of their very eyes and after five long and bitter years the Army meant nothing further to them. They wanted to get ashore and go home! Some returned soldiers amongst the lumpers sent messages to the men on the ships by heliograph and told them what the position was on the waterfront. They received the message back - 'say the word and we will bring these ships in ourselves and join you in the fight.’

McCallum prevailed on them to give him one more chance to get the government to see reason. They agreed, but only because they trusted him with almost a blind loyalty and devotion. The dispute had then become one of extreme and dangerous urgency. McCallum had a long secret conference one night with Inspector Sellinger of the Fremantle Police.

I was there at the age of ten. Sellinger was an extremely fine man. Intelligent, firm and most understanding of the gravity of the situation, and realised that action was required, and urgently. He informed the Commissioner in Perth and finally they prevailed on the Premier to come to Fremantle and meet the men immediately. Colebatch, this time, agreed. Unfortunately instead of coming down bravely by road, he chose to get hold of a launch and come down to the Harbour via the Swan River to a point near what was then 'F’ Shed. Between 'F’ shed and the wide road servicing the wharves was drawn up a large force of police armed with rifles and bayonets. The 'Tick-Tack’ well known on Australian racecourses soon went into operation between Perth and Fremantle. A section of the lumpers made their own decision. They went to the bridge over the Swan River at East Fremantle. When the Premier’s launch passed underneath they dropped a large iron bar onto it, missing the Premier and his party by inches and it passed right through the vessel tearing a hole through its hull. It was not far to 'F’ shed where the Premier and his party disembarked.

The Riot Act was then read publicly! This empowered the Police to take whatever action they considered necessary to preserve law and order. The command rang out to 'load’ then 'fix bayonets’ and McCallum raced to the top of the wooden steps leading from this point over the railway lines, and leading to a point near the main entrance to Fremantle Railway Station.

He turned to address all who were assembled. McCallum stood there, immaculate in his well-tailored tussore silk suit and called out to the multitude of desperate men below 'No! Stop you fellows. Listen to me. Do nothing foolish or hundreds of you will be killed. Leave this to me!’ Before they could do anything about it McCallum ran like the champion athlete he was to the other side of the road and faced straight up to the serried ranks of police. He called out to them in those strong, clear and commanding tones he could use with such enormous effect, 'Put down those bloody rifles.’ In spite of their officers in charge of them, but challenged by the ringing voice of the man who stood up on his own to confront them, they meekly submitted. McCallum called out 'Where is Colebatch?’ He found him and advised him to get the hell out of it and go back to his office in the old Treasury building in Perth and McCallum would follow him with some representatives of the Lumpers Union and they would settle this thing once and for all. Colebatch had no alternative but to agree. He was a very frightened man.

Unfortunately, in a short melee that occurred one policeman panicked when he discovered the men were armed with bombs, and he bayoneted Tom Edwards, a very fine young Australian who left a lovely wife, and a family of little children. Bill Renton, the Union President was hit on the head with a rifle butt when he tried to intercede and was badly wounded. However, he led the funeral procession the following day mounted on the traditional black charger and large white saddle cloth, with his head swathed in bandages. It was the largest funeral Fremantle had ever seen, but were it not for the fantastic courage of one man, McCallum, it could have been the funeral of hundreds of decent Australians.

Colebatch had no alternative but to accept McCallum’s terms. Work was resumed, but many of the old hands still remember it as one of the bleakest days in Australia’s industrial and political history. [25]

An account of the riot can also be found in Steadfast knight: A life of Sir Hal Colebatch by Hal G P Colebatch.

This dispute and others over the next few years saw unions in the 'official’ labour movement gain ascendency over 'bogus’ or 'nationalist’ unions, with resultant bitterness and divisions in the different labour sides. [26] In the aftermath of the riot, Colebatch, who had been unable to obtain a seat in the Legislative Assembly, resigned as Premier and James Mitchell took on the position. The 'McCallum' verses published in a Perth newspaper under the pen name 'Bricktop' capture the high drama and strong feelings arising from the Lumpers' dispute and its aftermath.

- Chorus - all in

Maccallum, Maccallum;

May every ill befall him.

Our one request, is kill the pest,

If you should meet Maccallum.- Commodore Coldback

When lately I set sail from Perth

To get one on the Lumpers,

On me they dropped the blasted earth

In overflowing bumpers.

I had to beat a quick retreat

Like some poor frightened baa lamb

And had to slip the premiership

All through that bloke Maccallum.- Chorus - all voices

Maccallum, Maccallum!

Tho Laborites extol him

No cause have we to sing with glee

The praises of Maccallum.

'MacCallum', by 'Bricktop’, clipping from unidentified Perth paper, 1919 [27]

Top left: The coastal trading ship SS Dimboola which was the focus of the 1919 'Battle of the Barricades' at Fremantle Wharf.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Bobbie Oliver. SS Dimboola, 1919. JCPML00568/6/1. Original held by Fremantle City Library Local History Collection: 2770B.

Top right: MLC for West Province Alex Panton (right) and Fremantle Lumpers' President Bill Renton, who was injured in the Fremantle Wharf riot on 4 May 1919.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Alex Panton MLC, and Fremantle Lumpers President, William Renton, with his head bandaged as a result of wounds incurred in the Fremantle Wharf riot, May 1919. JCPML00830/175/57

Bottom left: Funeral cortege outside the Fremantle Trades Hall, 9 May 1919, for Tom Edwards, killed in the riot five days earlier..

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Bobbie Oliver. Funeral cortege for Thomas Edwards at Fremantle Trades Hall, 1919. JCPML00568/5/2

Bottom right: Thousands of mourners attended Tom Edwards' funeral at Fremantle on 9 May 1919.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Large crowd at funeral of Tom Edwards, Fremantle, 9 May 1919. JCPML00830/175/47

Supporting the One Big Union movement

In 1919, in a move which brought it into line with the Federal organisation and the other state bodies, the ALF changed its name to become the Australian Labor Party (WA Branch) and McCallum continued as General Secretary.

Alex McCallum was a strong supporter of the One Big Union (OBU) movement of 1919-22, developed by the Industrial Workers of the World and with its main supporters in movements in New South Wales and Victoria. Its supporters proposed that workers form OBU and use direct action rather than arbitration to settle disputes.

In WA, support for the OBU may well have reflected a lack of confidence in the Arbitration Court to deal fairly with workers’ grievances. McCallum shared this distrust of the Court, sometimes preferring to put industrial matters in the hands of the Disputes Committee at Trades Hall rather than going down the route of arbitration. Cecilia Shelley, the first female Secretary of the Hotel, Club, Caterers’, Tearooms and Restaurant Employees’ Union in WA, met Mr McCallum, as she always called him, when she was a young union organiser. Speaking less formally of 'Alec’ in 1976, she recalled:

When I first met Alec I told him about the conditions in the Hotel’s restaurants and he was really horrified and told me what to do about it. I told him we were going to arbitration to get a new award and he explained to me that I should put the matter in the hands of the Disputes Committee at Trades Hall. Alec was really tremendously helpful and I don’t know what I would have done without his help. He did everything. He drew up a schedule of wages and working conditions; he did everything in conjunction with it… He not only did this for our union, he did it for every union. He was a strong man and he was a fighter...My union was in trouble all the time, lots of stop work meetings etc. Alec was the one who guided the whole thing and there was no flimsy strike talk…I used to run to him if there was any bother on. There were attempts to break up the union but Alex fixed it... As far as I was concerned, he was a terrific guy for the Trade Union movement. [28]

WA Labor Congresses in 1919 and 1920 supported the concept and a watered-down version of the OBU named the Workers Industrial Union of Australia, WA Section, was set up. However differing views of how the OBU should function, particularly in relation to the already existing Australian Workers’ Union (AWU), caused upheavals in the Party. More radical Labor men such as Alfred Callanan, pushed for more militant action and the OBU he set up in October 1920 was branded bogus by the AWU and the Westralian Worker newspaper. [29] The Worker’s editor, John Curtin, had previously supported the idea of a radical One Big Union as did his Victorian Socialist Party colleagues such as Hyett and Ross. Under constraint by the conservative AWU, which took over the Worker in January 1919, he fully supported the AWU 'as the only possible OBU for Australian conditions'. [30] Callanan was defeated and the Labor movement, facing problems of high unemployment as the Depression set in, continued its trend to moderation and away from militancy.

Left: Cecilia Shelley, first female Secretary of the Hotel, Club, Caterers’, Tearooms and Restaurant Employees’ Union in WA.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Bobbie Oliver. Cecilia Shelley, State Union Secretary 1920-1922, 1929-1967. JCPML00568/16/1. Original held by J S Battye Library of West Australian History: BA2749P.

Right: Alex McCallum (seated left) with other members of the State Disputes Committee, 1919.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Bobbie Oliver. State Disputes Committee, 1919. JCPML00568/6/2. Original held by Fremantle City Library Local History Collection: 2770A.

Private life and public celebrations

McCallum's heavy work load and long hours as General Secretary of the ALF meant that his family would not have seen much of him during his period at the Trades Hall. In 1912, his son Don started at Alma Forest School in Fremantle. Alex McCallum loved and cared for his family but the autocratic, demanding personality evident in his public life was doubtless present at home as well, with McCallum being the strong authority father figure, common for that turn of the century period. Don later recalled:

At no time did that small boy question or contest his father as to how his future life should be employed. His father had spoken. [31]

Alex McCallum was starting to learn the importance of holidays as a means of staying healthy while coping with the demands of his work. He purchased a farm, 'Koojarlee’, at Muntadgin where the whole family could relax and where he could further his dreams of breeding his beloved Clydesdale horses. At home in Fremantle, the family lived in a comfortable house with a large yard in Wray Avenue.

On the social front, McCallum's position in the Labor movement necessitated his attendance at a range of public events. Notably, Bessie and Alex McCallum were invited to a round of civic engagements celebrating the visit in 1920 of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, which included two balls, one State banquet and numerous receptions.

Top left: Formal portrait of the McCallum family, Perth, c 1920

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Bessie, Don and Alex McCallum. Perth ca 1920. JCPML00830/13

Top right: Alex with one of his Clydesdale horses.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Alex McCallum with Clydesdale horse, Muntadgin 193? JCPML00830/31

2nd top: The McCallum family's comfortable home in Wray Street, Fremantle.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. McCallum family home front lawn, Wray Avenue, Fremantle, 192? JCPML00830/113

3rd top: Livestock at the McCallum farm 'Koojarlee' at Muntadgin.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Livestock at the dam, Koojarlee, 192? JCPML00830/149

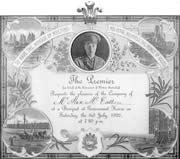

Bottom left: Invitation to attend a banquet at Government House to meet HRH Prince of Wales, 3 July 1920

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Invitation from the Premier to Alex McCallum to attend a banquet at Government House to meet HRH Prince of Wales, 3 July 1920. JCPML00838/1

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of Alex McCallum. Invitation to ball in honour of HRH The Prince of Wales, 7 July 1920. JCPML00821/1