INTERNMENT

We have many people of different nationality in our midst, especially in Fremantle. As individuals they are not responsible for the present state of affairs and against them we have no grudge or hatred. I would like to appeal to all our citizens to extend to these people that courtesy and consideration which we ourselves would appreciate if we found ourselves in their position.

The Mayor of Fremantle, Frank Gibson. (Bosworth, 1996)

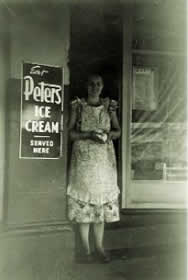

Italian internees with their personal belongings in Barmera, South Australia, 1943.

Courtesy Australian War Memorial: Negative No. 123060

MASS INTERMENT NOT BEST POLICY SAYS PRIME MINISTER

Canberra, Wednesday. - Action had already been taken to intern those alien and other elements in Australia who, if left at liberty, would represent a menace to security, the Prime Minister (Mr. Curtin) said today in the House of Representatives.

Mr. Curtin said the position was constantly under review and such internments were effected as the situation required.

It was not policy to resort to mass internments, as such procedure did not materially add to the security achieved by the present course of action.

Measures believed to be effective had already been taken to investigate and restrict the activities of female enemy aliens, and female subversive elements of other nationalities.

Ethnicity was a factor in how people experienced the war. The Menzies Government introduced the National Security (Aliens Control) Regulations in 1939. The regulations were considered by civil libertarians to be draconian. The ‘onus of proof’ was placed on individuals to show that they were not ‘enemy aliens’ and should not be interned.

Internment in Australia was kept to a minimum partly due to practical concerns such as cost – investigating every non-British person would be expensive; and economic disadvantage – detaining non-British residents could mean leaving jobs unfilled. However, about 15% of resident Italians, 33% of Germans and almost all Japanese became internees for the duration of the war.

Enemy Aliens

All aliens were required to register at their nearest police station while ‘enemy aliens’ were subject to restrictions on their movement beyond their police district and had to report to their Aliens Registration Officer every week. Cameras, guns and radios capable of overseas transmission were confiscated. Australian women married to foreigners automatically lost their British nationality. However, the Australian Nationality Act of 1937 gave them the option of renouncing their husband’s nationality and taking out British naturalisation for themselves. As a general rule women weren’t interned.

By January 1943 a total of 16,830 prisoners-of-war and internees were detained in Australia. These groups were kept in separate military-run camps. Prisoners-of-war were enemy soldiers while internees were civilians who were deemed to be potentially dangerous to national security.

German internees of No. 1 Camp, Tatura Internment Group, using the workshop to reuse salvaged material into comforts for their own benefit.

Courtesy Australian War Memorial: Negative No. 030205/01

Airzone wireless capable of picking up short wave broadcasts, c.1935. Courtesy Fremantle Light and Sound Discovery Centre.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of JCPML. Agfa box camera, 1930. JCPML00736/1

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of JCPML. Baby Brownie Bakerlite camera manufactured between 1934-41. JCPML00736/2

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of JCPML. Six-20 Brownie Junior manufactured between 1934-42. JCPML00736/3

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of JCPML. No.2 Folding Autograph with its carry case, manufactured between 1915-26. JCPML00736/4

Towards the end of the war when it was obvious that Australia was no longer a target for invasion and shortage of manpower was a major concern, most internees were released. From 1944 no new internments took place, only restriction and surveillance orders remained.

Most local radio stations in Australia broadcast on the medium wavelength band. Dual wave wireless sets could pick up both medium wavelength and short wavelength transmissions. Broadcasts transmitted on ‘short wave’ would travel much further because the radio waves bounced off the ionosphere as they travelled around the Earth. These types of transmitters were confiscated because of fears that ‘enemy aliens’ could pass on information that would harm the Allies.

Airzone was an Australian company that made radios between 1925 and 1946.

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY

Man of his Word

This country could and should afford a welcome and a decent opportunity to every man or woman who…seek[s] to come here…He is the kind who, given adequate foreknowledge and placed on an equal footing with the rest of the community from the day of landing in Australia, is prepared to map out his own destiny in his own way. Energetic measures should be taken to encourage that sort of citizen to come to Australia.

(John Curtin, 1927)

Increasing the population

In May 1944, Curtin declared there was a need to increase Australia’s population of approximately 7 million because war had revealed deficiencies in the country’s manpower. In 1947 Australia agreed to accept displaced persons through the International Refugee Organisation. The government paid their passage and they worked for two years in designated jobs.

Arpad and Lujza Szedlak with their daughters Gabrielle and Marta on the refurbished troop ship General Hersey, 1950. Courtesy Gabrielle Jones (nee Szedlak)

In the early postwar years many emigrants came to Australia to escape the continuing misery in Europe which was battle-scarred after six years of war. From the end of the war until 1949 more than 500,000 people arrived in Australia to take up jobs in the rapidly expanding areas of manufacturing and construction and in the expectation of having a higher standard of living.

Arthur Calwell became Minister for Immigration in 1945 and was responsible for initiating and promoting a vigorous immigration policy for Australia. Between 1942 and 1945 Calwell had chaired the Aliens Classification and Advisory Committee and came to believe that ‘most [internees] were excellent citizens’ and he ‘had few fears about bringing more such people to Australia’ after the war. (Margaret Bevege, 1993) He saw the benefit in widening immigration policy to include other European peoples and promoted the term ‘New Australians’. However, Calwell rejected the idea of allowing Asians to settle in Australia. He, like Curtin and others of this generation, was committed to the ‘white Australia’ policy. The Australian Labor Party in particular had concerns about migrants competing for jobs with Australians. It was the defence of Australia which provided the driving force to increase immigration.

White Australia Policy

The ‘white Australia’ policy dates back to Australian federation in 1901. The first acts passed by the Federal parliament were the Immigration Restriction Act and the Pacific Island Labourers Act which were intended to protect Australia against invasion by non-Europeans and to remove such non-white immigrants from the country. The Australian Labor Party supported a ‘white Australia’ policy on the basis that it was essential to protect Australians’ high standards of living. Non-European workers were feared because of their supposed willingness to work for longer hours and lower wages than ‘white’ Australians.

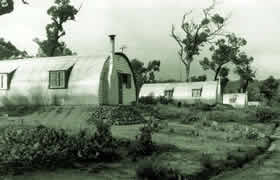

Nissan huts at the Graylands Hostel for British migrants (Western Australia), c.1951.

Courtesy Nonja Peters

As a member of the ALP, John Curtin supported a ‘white Australia’, believing that ‘the white and coloured races, for biological and economic reasons, are better apart, each in its own country…[W]e are utterly opposed to the interference by white nations in the internal affairs of Asia, just as we are opposed to coloured immigration to Australia.’ (John Curtin, 1928)

By 1943 Curtin seems to have had some misgivings about the ‘white Australia’ policy. According to Frederick Smith, Australian United Press bureau chief and Canberra manager:

Curtin is anxious that Australian papers should avoid raising the White Australia issue or even referring to the term ‘White Australia’ at the present juncture. He is concerned about the effect on the coloured people, particularly the Chinese, who are on our side in the war. He points out that there is no legal term ‘White Australia’ which is a term arising out of a policy legally set out in the Alien Immigration Restriction Act.

(Clem Lloyd and Richard Hall, 1997)

Camp conditions were not luxurious and life was based on a military regime of reveille, inspections, lights out, bed checks and block leaders. Initially, there was a poor standard of hygiene and migrants were expected to wash their utensils in communal washing bowls, while toilets and showers had no doors and there was no hot water.