Federal Powers referendum

In the decade 1918 to 1928, Curtin contributed significantly to the labour movement in Western Australia. In 1920, he was elected president of the Western Australian District of the Australian Journalists Association [AJA]. He was a delegate on the ALP's Fremantle District Council, and a member of the ALP State and Federal Executives. [22] He also gave lectures, campaigned for ALP candidates and joined deputations to the Premier to discuss issues such as unemployment. [23]

In 1926, through the pages of the Worker, he opposed the conservative Bruce-Page Federal Government's proposed Federal Powers referendum. Curtin argued [24] that, contrary to powers sought by Federal Labor governments in earlier referenda, Bruce proposed to establish a non-government authority to take over powers held by States. Curtin concluded that the people should never vote for proposals that divested them of the powers conferred upon them by the Constitution. When put to the vote, the referendum failed as its predecessors had. [25]

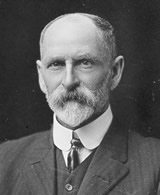

Doing 'the work of two or three people' [26] created pressures on Curtin's home life and strained his health. From 1920 to 1922, his was frequently ill; a number of his editorials were written by his father in law, Abraham Needham [27].

Abraham Needham (Elsie Curtin's father)

Abraham Needham (Elsie Curtin's father)

aged c. 58 ca 1918.

Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00376/225.

Conference of the League of Nations at Geneva

In 1924, Curtin represented Australia at the Sixth International Labor Conference of the League of Nations at Geneva from 16 June to 5 July. He was one of 127 credentialed delegates from 40 countries. Curtin succeeded in achieving his aims on both of the committees of which he was a member.

He successfully opposed the proposal for an International Convention to enforce the disinfection of wool against anthrax, because it would result in Liverpool (where the disinfection would be carried out) being the only European port of entry and distribution for Australian wool.

Despite stiff opposition from the employers' representatives, the Committee on Night Work in Bakeries, on which he also served, succeeded in drawing up a Draft Convention prohibiting night baking. Curtin's experiences in Geneva, where employers and workers met 'on a common platform to consider proposals for the more humane regulation of industry', left a deep impression upon him. [28]

John Curtin (front, 2nd from right) with delegates to the ILO Convention,

John Curtin (front, 2nd from right) with delegates to the ILO Convention,

Geneva, 1924.

Records of the Curtin Family.

JCPML00376/1.

Chairing the Child Endowment Committee

In 1927, he chaired a committee investigating child endowment, which recommended a government payment of thirteen shillings and five pence a week per child to families with more than two children.

When the resulting Royal Commission ruled against instituting a child endowment scheme, Curtin and the other Labor delegate, Mrs Muscio, submitted a minority report, dissenting from the majority position that 'the advocates of a plan of family assistance' had not established that the Basic Wage was insufficient to provide adequately for more than two children. [29]

Standing for the Federal seat of Perth

While these activities demonstrated Curtin's capacity for leadership on a variety of platforms, he was a victim of internal strife within a WA labour movement still recovering from the bitterness of the conscription split. In 1919 - which he described as a year when 'we allowed the days to go by in futile controversies with each other' [30] - Curtin unsuccessfully stood for the Federal seat of Perth. He felt unsupported by the State Executive, while they believed that he failed to keep them informed of his intentions. After a bitter, abusive campaign, in which he was personally targeted, Curtin secured only about one third of the vote. [31]

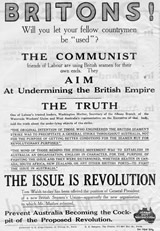

But this defeat indicated more about the anti-Labor attitudes of electors in 1919, when even Senator Needham lost his seat, than personal dislike of Curtin. He did not contest the 1922 election, but suffered a second defeat in 1925 when he first stood for Fremantle. [32]

Conflict with the Seamen's Union

Earlier in that year, Curtin had been targeted by a section of the union movement, after he refused to publish a letter in the Worker, criticising the actions of the Collier State Labor Government and the ALP State Disputes Committee in the long-running Seamen's dispute. Although the letter's author, George Ryce, claimed to be a member of the Federated Seamen's Union, it was later revealed that his membership was bogus. Curtin was unaware of this when he refused to publish Ryce's letter because it contained 'gross untruths' and libeled the State Disputes Committee. In retaliation, the Union declared Curtin 'black' and stated that they would refuse to take to sea any vessel on which he was a passenger.

This time, Curtin was in no doubt of the ALP's support. The State Executive reacted swiftly, expelling the union. The FSU was not re-affiliated with the ALP until long after the offending resolution was expunged from its books in mid 1925. [33] But the backlash from the Seamen's strike, which affected all of Australia's major ports, was felt in the 1925 Federal election, and Fremantle turned to the independent candidate, local businessman William Watson. Curtin 'blamed his loss on a electorate made fearful by government talk of "revolution, of strikes, of Communism"'. [34]