Anti-conscription manifesto

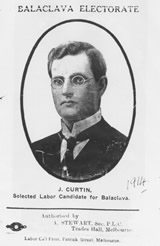

In 1916, when the issue arose of conscripting men for military service with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in France, John Curtin was at a low point in his life, and between jobs. After an unsuccessful attempt to stand for the Victorian seat of Balaclava in the Federal election, suffering from depression and alcoholism generated by pressure of work, the advent of the war and a growing pessimism about the capacity of Socialism to reform the world, he resigned from his position as Secretary of the Timber Workers' Union, and served for a short time as an organiser for the AWU. [1]

The Congress of Australian Trade Unions held in Melbourne in May 1916 'steadfastly opposed both military and industrial conscription' [2] and set up an executive committee to organize an anti-conscription campaign, with E.J. Holloway as secretary and Curtin as organizer. Unfortunately, Curtin did not hold this post for long; exhaustion and alcoholism caught up with him. After failing to show up for a meeting of the Socialist Party Sunday School, which he was meant to be addressing, he admitted himself to a convalescent home. [3] Following his recovery, with conscription now a very real possibility, in July 1916, the Anti-Conscription Committee appointed him as its full-time national secretary. Although this seemed like a remarkable vote of confidence, according to E.J. Holloway, Curtin justified it by doing 'a wonderful job' and in particular because of the value of his journalistic experience. [4]

As the Censor had banned anti-conscription propaganda, including printing news of the campaign's activities, Curtin and his colleagues had to find other ways of getting their message across to the public. Labor Call printed the anti-conscription resolutions of the Melbourne Congress in a leaflet titled 'The Anti-Conscription Manifesto', which detailed reasons why Australians should reject conscription, including that conscripted soldiers would be forced to act as strike breakers and that workers would be placed under conditions of martial law. [5] In August, the Victorian police raided the Melbourne Trades and Labour Council premises, and seized copies of reports and the Manifesto. The Minister for Defence, George Pearce, who was a Labor Senator for Western Australia, sanctioned the raid. In Western Australia, a struggle had been going on in the labour movement, which was evenly divided between pro- and anti-conscriptionists. The ALP State Executive asked Pearce to explain his action, and emphasized the need for free speech. [6]

Although Pearce's bans and raids may have appeared to place insurmountable odds in the Anti-Conscription Campaign's path, according to Holloway, it was 'manna from heaven' because 'Indifference in many was suddenly turned to curiosity and interest. All [of] the world wanted copies [of the Manifesto]'. [7]

Election pamphlet, Balaclava 1914. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00376/62.

Election pamphlet, Balaclava 1914. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00376/62.

Flyer, Australian Trades Union Anti-Conscription Congress, Manifesto No. 2, 2 September 1916. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00398/7.

Flyer, Australian Trades Union Anti-Conscription Congress, Manifesto No. 2, 2 September 1916. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00398/7.

This copy of the flyer has a note written by John Curtin, '100,000 circulated'.

Speaking on the Yarra Bank

Banned from speaking in many halls in central Melbourne, the anti-conscriptionists had to resort to the traditional speaker's corner, the Yarra Bank, where they attracted large, and often hostile, crowds. Even without the inflamed emotions provoked by the conscription issue, the Yarra Bank crowds could be an overwhelming experience for would-be speakers. Labor activist Jean Beadle recollected the daunting experience of standing before 'a vast sea of faces' at the 1898 May Day rally. [8]

Here, however, Curtin excelled as an orator, although he lacked the skills to protect himself from a violent mob. A fellow speaker, Fred Riley, recalled that on such occasions he used to untie his shoelaces, in order to get rid of his shoes quickly if he was given a dunking in the river. Curtin was horrified: 'They wouldn't do that - would they?' Riley assured him that the mob was capable of anything and asked Curtin if he was afraid. Curtin said 'No' but that he was not a strong swimmer. Nor could he fight. Riley said: 'I can [fight] - but I want someone to guard my back'. Curtin promised to do his best, but after another particularly rough meeting, he admitted that he had been 'paralysed with fear' and would have been useless. 'I wish I had your courage', he told Riley, who replied, 'I wish I had your oratory'. [9]

Nevertheless, Curtin kept speaking and his fellow speakers testified to his brilliance as an orator. In September 1916, a month before the date set for the referendum in which Hughes hoped to gain the people's assent to conscript men for overseas service, at the government's instigation, the Governor-General issued a Proclamation, ordering all single and childless 'male inhabitants of Australia, aged from 21 to 35 years', to enlist in the armed forces. The trade unions called a one-day general strike in protest on 4 October. Curtin spoke to a crowd of 50,000 on the Yarra Bank. On such occasions, he rarely resorted to 'rabblerousing', preferring to put a logical argument, backed by statistical evidence that conscription would not produce the numbers of men deemed necessary to maintain the war effort. After the strike, he departed on a speaking tour around Victoria - including the strongly pro-conscription town of Charlton, where he had lived for three years as a child - and to other Australian states. Despite the ever-present threat of violence, he was never beaten up, but once was hit by an egg on the back of his neck, an experience that he found so unnerving that he ceased talking and left the meeting. [10]

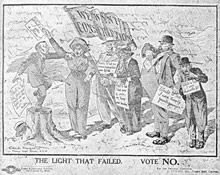

Anti-conscription cartoon, ca 1916. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00399/3.

Anti-conscription cartoon, ca 1916. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00399/3.

![[Yarra bank meeting], 1923, painting shows a trade union meeting on the banks of the Yarra. Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.](pics/SLV_b28692s.jpg) Painting of a trade union meeting on the banks of the Yarra by Patrick Harford. People are listening to a speech given by Fred Riley.

Painting of a trade union meeting on the banks of the Yarra by Patrick Harford. People are listening to a speech given by Fred Riley.

[Yarra bank meeting], 1923.

Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria, image no. b28692.

Three and a half days in prison

Despite the Australian people rejecting conscription by a narrow margin on 28 October 1916, those who had failed to comply with the compulsory call up were pursued. Curtin was one. Having ignored a summons to attend court, he was arrested on 12 December and imprisoned.

He was confined with Norman Grant, secretary of the No-Conscription Fellowship, 'for fourteen hours a day to a small, unventilated cell, with a bucket for a toilet and a hard floor as their bed', although Curtin was permitted to retain his own clothes. [11]

Sentenced to three months imprisonment for failing to enlist, Curtin and other conscientious objectors were released after friends interceded on their behalf to Senator Pearce. Nevetheless, Curtin's three-and-a-half day stint in prison was a traumatic experience. [12]

After his release, despite mental and physical exhaustion, Curtin continued to address packed gatherings. But he needed a livelihood, and with the help of some influential ALP members, he secured a post as editor of the Westralian Worker in Perth. As 'Worker' editor from 1917 to 1928, Curtin produced his greatest body of work written from a personal perspective in a series of weekly editorials. This period, culminating in Curtin's election to the Federal seat of Fremantle in 1928, has been imbued with particular significance by a number of students of Curtin's life, who see this as his transition from political radical to moderate. Such examinations have included scrutinising Curtin's changing position on conscription, from staunch anti-conscriptionist in 1916-17 to a Prime Minister who enforced and expanded military conscription in World War II to include service in areas of the South-West Pacific.

The call-up notice for John Curtin to attend Percy Street Drill Hall, Brunswick, 31 October 1916 or face a penalty of six months imprisonment under the War Service Regulation.

The call-up notice for John Curtin to attend Percy Street Drill Hall, Brunswick, 31 October 1916 or face a penalty of six months imprisonment under the War Service Regulation.

Records of the Curtin Family, JCPML00402/12. Click image for more details.

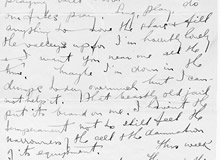

Excerpt of Letter from John Curtin to Elsie Needham, 27 December 1916, p. 7. Curtin refers to his time in jail.

Excerpt of Letter from John Curtin to Elsie Needham, 27 December 1916, p. 7. Curtin refers to his time in jail.

Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00402/18.

Click image for more details.