![]()

In the weeks and months which followed the outbreak of war in September 1939 Menzies had to decide on the nature and extent of Australia's commitment to a distant war but one in which Japan, unlike the situation in 1914, was no longer an ally. In these circumstances, Menzies was reported by his biographer as asserting to colleagues that the decision to send an expeditionary force to Europe and the Middle East had been 'forced upon him' to some extent by the British who had 'a quite perceptible disposition to treat Australia as a colony'1. However, the fact remains that Menzies did not have to deal with an immediate threat to Australia's homeland, and his hopes that war with Japan was not inevitable, accounted at least in part for the decision in 1940 to send an Australian Ambassador to Tokyo at a time when Australia's only other independent overseas mission was in Washington. Indeed, in many respects there were strong similarities between Menzies' policies throughout his almost two year term as war time prime minister and the line taken by Prime Minister Hughes during the First World War: namely that Australia should focus its efforts on obtaining a seat at the decision making tables in London and having a voice in the making of empire military strategy and foreign policy making.

Robert Menzies at Sydney opening of War Savings Week, 14

October 1940.

Robert Menzies at Sydney opening of War Savings Week, 14

October 1940.

JCPML. Records of Robert Menzies. Robert

Menzies at Sydney opening of War Savings Week, 14 October 1940.

JCPML00916/12.

Original held by National Library of Australia: MS 4936 Series 9,

Box 342

from 'business as usual' to 'unlimited war effort'

The other major difference between Menzies' and Curtin's role as wartime leaders was that for most if not all of Menzies' term he had difficulty persuading the Australian voting public that the war situation required major sacrifices on the home front. This was particularly evident during the so-called Phony War period, during which time Menzies himself had coined the phrase 'business as usual',2 and continued up to and beyond the September 1940 election in which Menzies lost his independent majority in the House of Representatives. In this regard, there is no better case study than the ongoing difficulties the government faced in introducing petrol rationing.3 Indeed, it was not until Menzies' last month as prime minister that really substantial regulation of petrol supplies came into operation. In addition, Menzies' absence for several months in the UK during the first half of 1941, even though one of his prime motives was to secure a more substantial British commitment to the defence of Singapore, meant that during this period his direct contribution to the war effort at home was limited - in the words of his biographer it was 'a failure'.4 Not only did he fail to have Churchill acknowledge the possibility of Singapore falling to a land-based attack but the war situation in any case simply did not allow Britain to divert significant military resources to the defence of Singapore. During his time in the UK Menzies also encountered the total rejection of his attempts to improve wartime relations with the Republic of Ireland. Most damaging of all, both before and after his return to Australia, he had great difficulty in getting across to the electorate the part he had actually played (or not played) in the decision-making on the disastrous Greek and Crete campaigns.

Advertisement for "National" Gas Producers designed to

allow vehicles to run on charcoal instead of petrol.

The Bulletin, 17 September

1941

Back in Australia Menzies, in a broadcast to the nation, declared that an 'unlimited war effort' was essential and that 'We have in fact reached a point where your alleged rights or mine don't matter'.5 The changes he proposed included overhauling the list of reserved occupations; the direction and use of manpower, and of the services of women; the reexamination of both civil production and consumption with non-essential imports 'cut to the bone'; the introduction of various administrative changes to streamline the direction of the war effort; the prohibition of strikes and lockouts; and moves to limit luxury spending.6 At the same time however, Menzies' problems with his own party made his position increasingly untenable at the very time that press hostility to his government increased significantly following the government's introduction of newsprint rationing. As the threat from Japan mounted the Cabinet did agree in August that Menzies should return to 'represent in the British War Cabinet the dangers and needs of the antipodean Dominions'.7 Without agreement from Curtin, however, the political situation did not allow the visit to take place and a few weeks later Menzies lost office.

In December 1941 the head of the Defence Department, F.G. Shedden, wrote to Menzies that

Tribute has yet to be paid to the great foundations laid by you at a time when you lacked the advantage of effect on national psychology and morale of a war in the Pacific.8

In similar vein war historian Paul Hasluck wrote that 'precious work had already been done' and by the time the war spread to the Far East 'many of the initial difficulties and most of the routine tasks organizing a nation for war had already been mastered'.9 Unfortunately for Menzies, a lack of trust and party political problems alike ensured that he could not continue the work he had begun.

|

|

View home movie footage of Prime

Minister Menzies at a march past of AIF troops in the Middle East

in February 1941.

Australia to England via Tobruk and

Benghazi: [Menzies Wartime Tour], 1941. National Film & Sound

Archive: Title No 5202. Courtesy Heather Henderson

To find out more about Menzies' wartime tour

abroad, go to

Robert

Menzies’ 1941 Diary

on the website of Old Parliament House, Canberra.

with such a dire threat to the homeland political and community opposition to increased governmental controls virtually disappeared

In sharp contrast to Menzies, Curtin found himself, within a few weeks of taking office, confronted with such a dire threat to the homeland that political and community opposition to substantially increased governmental controls virtually disappeared. This situation lasted from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour at least until the end of 1942 when Curtin undertook his successful tactical battle within the Labor Party to achieve the adoption of limited measure of military conscription for the defence of the nation.

Under Curtin's leadership, differences with Britain concerning war strategy rapidly came to a head in the famous cable war between Curtin and Churchill in February 1942. In the previous month Curtin's Cabinet had pressured Churchill into sending a division to Singapore rather than Burma, an action which cost the British a large number of troops and for which in the words of historian David Day 'Churchill never forgave Australia'.10 While the Curtin Government was not responsible for the decision to bring back two divisions of Australian troops from the Middle East the subsequent dispute over whether these soldiers should be diverted to Burma culminated with Curtin's insistence that Churchill countermand the order he had given to that effect.11 Menzies, for his part at this time, agreed with Curtin that Australia should concentrate all its available forces in the north of Australia rather than in the islands to the north but at the same time he still urged for reinforcements from Britain to be sent to defend Burma.12 By this time, however, Menzies was on the back bench in Parliament and it was not until after the August 1943 election that he once again began to play as a role as a significant critic of the government's performance.

Curtin's New Year message for 1942 in which he looked to the United State for assistance has had its critics then and since but essentially Australians and most historians accepted at the time and since that the close relationship with the USA in general, and with General Macarthur in particular, was essential to Australia's capacity to avoid foreign invasion. Whatever the reality of Japan's intentions and capacity at the time - as John Edwards has said 'the Battle for Australia...never took place'13 - the fact remains that the threat to the homeland seemed so obvious and apparent, certainly until well into 1943, that Curtin's leadership was accepted without question amongst the population at large.

Government advertisement 'So that they may turn the wheels, Invest

in the War and Works Loan', 1941

The Bulletin, 7 May 1941

'there can be no distinction between solders and civilians. Every one has a battle station'

The United States became Australia's ally because it had been attacked itself but Curtin's task was to convey to the Australian people the message that

We are at a stage in our history when the struggle for survival as a nation overrides every other consideration.14

and this was a struggle in which everyone had a role to play. In appealing for war time loans he broadcast to the nation

there can be no distinction between solders and civilians. Every one has a battle station... There is much money in circulation...The only justification for possessing it is that it should be saved and lent to the nation for the nation's need.15

Similarly, in launching an austerity campaign:

only by an austere way of life can we muster our national strength to the pitch required for victory...In this hour of peril I call on each individual to ... go to their tasks guided by a new conscience and a new realization of their responsibilities to their nation, and to each individual member of it.16

Given Curtin's humble origins and self doubts for much of his life, his capacity and skill in inspiring trust, loyalty and capacity for self sacrifice are consequently all the more remarkable.

Commonwealth Rolling Mills advertisement 'Australians are Making

Weapons of Victory', 1942

The Bulletin, 13 May

1942

the 'Brisbane Line' ... intractable unionists... Curtin faced mounting problems

By the middle of 1943, however, as the immediate invasion threat dissipated the political difficulties at home began to return commencing with the controversy concerning the part played by firebrand Minister and former Lang Laborite Eddie Ward and his accusations concerning the so-called 'Brisbane Line'. Ward had accused the previous Menzies Government of having a plan to abandon northern Australia to the Japanese in the event of an invasion from the north and Curtin, in the face of criticism that he should repudiate Ward, was obliged to establish a Royal Commission to investigate the issue. Nevertheless, his government was convincingly returned to power in the August 1943 election winning a majority in both houses for Labor for the first time since 1916, though with Menzies back at the helm as Opposition leader, party political opposition was building up within the Parliament.

In this new environment Curtin had to maintain community support for the war effort while ensuring that Australia was relieved of some of her military commitments to enable her to boost food production at home, yet all the while maintaining a sufficient military presence during the war to ensure significant influence at the peace table. It was not part of Macarthur's plans to use Australian troops as part of his advance towards Tokyo and hence Curtin was able to secure agreement limiting the Australian military contribution while still insisting that to ensure a seat at the peace table there would be 'a minimum fighting strength below which Australia would not go'.17

During the second half of 1944 Curtin faced mounting problems with the defeat of the government's referendum proposals - introduced largely at the behest of Attorney General Dr Evatt and seeking a range of permanent new powers for the Commonwealth Government - and continuing disputes with intractable unionists on the coalfields. Following a major heart attack in November 1944, ill health meant that Curtin's personal role declined to the point where most of the real decisions had to be made by others. However, the directions the government took in those last eight or so months were still substantially those that Curtin himself had foreshadowed and sought to bring about.

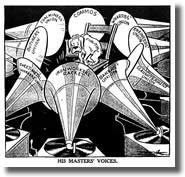

'His masters' voices'

Cartoon by John Frith

The Bulletin, 21 July

1943

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|