Curtin's ship docked at San Francisco on 19 April, and almost immediately he embarked on a concerted campaign of public diplomacy. Before 50 journalists in San Francisco, he not only stressed that Australia's war effort had been 'magnificent' but also suggested that his upcoming meeting with Roosevelt would deal with 'how we shall shape things with each other and the world after the war.' 54

After a long and cold train journey, Curtin finally arrived in Washington four days later, on 23 April, where he was met by Cordell Hull, who led a brief ceremony at Union Station before the Prime Ministers' party checked in to Blair House, just across the road from the White House. Curtin's first impression of the American capital was not particularly favourable. When an Australian journalist told Curtin that he would be receiving around the clock Secret Service protection, Curtin was aghast. This was 'awful!' he exclaimed - and it marked a clear contrast to Australia, where 'public men don't have to fear violence.' 55

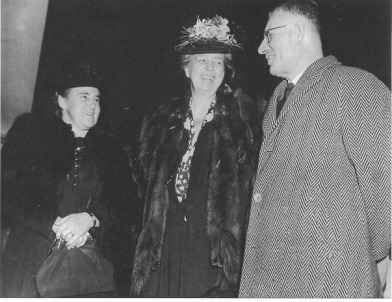

Over the next five days, part of Curtin's time was taken up with the social and public aspects of diplomacy. With Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady, determined to repay Australia for the hospitality she had received a year earlier, official Washington gave Curtin's party the full red-carpet treatment. The White House hosted its first state dinner since the start of the war, a departure that caused quite a stir amongst social commentators. 56 More than 80 leading American reporters also packed in to Curtin's press conference, anxious to pepper him with questions about Australia's ambitions. And they left suitably impressed with his open and 'quick-witted responses' on issues ranging from the successful war effort in the Southwest Pacific to his calls for as many Americans as possible to migrate to Australia. 57

But mostly, Curtin faced an intensive round of private meetings with many of the administration's leading players, including the Director of War Mobilization, the Navy Chief and the Secretary of State. On 25 April, Curtin then flew down to South Carolina to meet with Roosevelt. After a lunch that also included the President-Elect of Costa Rica, Curtin and Roosevelt met alone for almost an hour.

From the one record of this meeting, as well as Curtin's comments in the next few days and weeks, it seems that the two men discussed three issues: the ANZAC agreement, relations with the Soviet Union and general post-war matters. To some extent, their meeting was a success, with both leaders using their time to explore their very similar visions of the world. As Curtin stressed in public, his discussions with Roosevelt had focused on 'post-war problems, including . . . insurance against future aggression and the means needed to remove the fear of want and social insecurity for all mankind. The President and I,' Curtin declared, 'found ourselves like-minded on these matters.' According to the private record, the two men also - predictably - blamed Evatt for the recent tension surrounding the ANZAC agreement, with Curtin distancing himself from the initiative by adding that the whole pact had been drafted in an 'excess of enthusiasm'. 58

That day, 25 April, also saw the most memorable public episode of Curtin's time in America. Early in the afternoon, while Curtin was still meeting Roosevelt, the White House press office announced to reporters that a major statement, 'of interest to the world', would be released at 6. The media held its breath. Everyone expected an invasion of France at any moment. Perhaps the White House would reveal that this pivotal operation was finally underway. Perhaps it might even announce that Nazi Germany had surrendered. Throughout the afternoon, expectant journalists packed into the West Wing, swapping rumours. When the statement was put back another forty minutes, tension mounted to fever pitch. Then, at 6.40 the White House finally unveiled its news. In one terse sentence, it merely stated that the President of the United States had met with the Prime Minister of Australia.

It was a symbolic moment. Curtin's meeting with Roosevelt, which promised so much, had ended in a distinct anticlimax. American reporters, who'd been primed to expect a much bigger headline, were particularly savage. 'The 16-inch cannon that was expected to go off', proclaimed Arthur Krock of the New York Times, 'turned out to be a pop gun.' 'With all of America jittery', complained another reporter, 'with millions of parents on the extreme edge of their anxious seat', this was a cruel 'Hollywoodish prank.' 59

As with the media reaction, so with the substantive talks: they also turned out ultimately to be a letdown. In theory, of course, Curtin and Roosevelt now had a chance to build up more than just a close personal rapport; they also had a perfect opportunity to discover just how much they agreed on key issues. In practice, however, their actual meeting was far too short to make much of a difference. They simply didn't have time to discuss issues like post-war trade relations, domestic reconstruction, or the framework for the new United Nations organization. Far too much was left unsaid. And certainly nothing happened to deflect Curtin from his determination to go onto London and push for his Empire Council, which he hoped would strengthen the machinery of imperial governance.

The simple reason for the meeting's brevity - and its lack of a real result - was ill health. By the spring of 1944, these two great leaders were both clearly ailing. The stress of wartime leadership, combined with their large nicotine intakes, had taken their toll. Roosevelt was in a particularly bad way. The gruelling journey to Tehran and back in late 1943 had left him in a weakened state. By March 1944, having not shaken off what he thought was the flu, Roosevelt was examined by a heart specialist who was highly alarmed. With his blood pressure hovering at dangerously high levels, the President was packed off to South Carolina to rest. Throughout April his doctors were so worried about the state of his health that they confined him to no more than four hours of work each day - two hours for appointments and two more for paperwork. 60

As a result, Roosevelt was not in Washington to greet Curtin. He did not attend the state dinner. He was not at the White House when Eleanor Roosevelt hosted the Prime Minister for the night. And Curtin therefore had to fly down to South Carolina for his one brief meeting with the sick President. For his part, Curtin was probably relieved, if only because he had his own health problems. After a couple of days of gruelling meetings with some of the administration's major players, on 26 April Curtin had to cancel the remainder of his engagements and rest up because of a back pain. 61 His wife thought his ailment was caused by anxiety about his upcoming flight to London. But reporters soon speculated that Curtin, like Roosevelt, was suffering from high blood pressure. 62

Prime Minister John Curtin & Mrs Curtin being met at Washington by Mr Cordell Hull & Mrs Hull (Secretary of State, USA) 23.4.1944. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00376/107.

Prime Minister John Curtin & Mrs Curtin being met at Washington by Mr Cordell Hull & Mrs Hull (Secretary of State, USA) 23.4.1944. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00376/107.

Elsie and John Curtin with Mrs Franklin D Roosevelt, USA, 1944. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00004/34.

Elsie and John Curtin with Mrs Franklin D Roosevelt, USA, 1944. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00004/34.

PM John Curtin with Sir Owen Dixon (Australian Ambassador to USA) Washington, 23 April 1944. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00376/112.

PM John Curtin with Sir Owen Dixon (Australian Ambassador to USA) Washington, 23 April 1944. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00376/112.

USA Vice-President Wallace meets John Curtin, Washington, 24 April 1944. Records of Lloyd Ross. Original held by National Library of Australia MS 3939, Series 11, Folder 66. JCPML00617/66/30.

USA Vice-President Wallace meets John Curtin, Washington, 24 April 1944. Records of Lloyd Ross. Original held by National Library of Australia MS 3939, Series 11, Folder 66. JCPML00617/66/30.

Mrs Curtin's racy story of her trip. Argus, Friday, 21 July 1944. Click to view full article. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00964/140.

Mrs Curtin's racy story of her trip. Argus, Friday, 21 July 1944. Click to view full article. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00964/140.

Mr Curtin ordered complete rest. Crayton Burns, Argus, 7 November 1944. Click to view full article. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00964/143.

Mr Curtin ordered complete rest. Crayton Burns, Argus, 7 November 1944. Click to view full article. Records of the Curtin Family. JCPML00964/143.