BY DAY SHE SERVES

Man of his Word

Woman has been able to assert a degree of economic independence never previously attained. The home remains her citadel, but factory and workshop have become her arena. I have done my best in the face of an age-old law to have women paid on their merits. I see no reason why a woman should be paid less than a man for the same work.

(John Curtin, 1943)

For some women the war provided unprecedented opportunity, for others it was a cause of great unhappiness.

Joining Up

In 1941 the Federal Government gave its approval for women to join the armed services – Women’s Australian Auxiliary Air Force (WAAAF), Women’s Royal Australian Navy Service (WRANS), Australian Women’s Army Service (AWAS) or the Australian Women’s Land Army (AWLA). Many of the tasks performed by servicewomen were in traditionally feminine roles such as nursing, cooking, cleaning and typing. By mid-1943 there were over 46,000 Australian women in the services.

Women in Industry

Women’s participation in the workforce increased by 31% between 1939 and 1943 as women found work in factories and farms and were able to take up positions in country areas as teachers and nurses.

Australian Women’s army personnel at their positions on the anti-aircraft height and range finder and telescope identification equipment, Randwick NSW (1945).

Courtesy Australian War Memorial: Negative No. 085416

However, opportunities for women were restricted by the numbers of men enlisting and the rate of expansion of manufacturing and war-generated industries. Women entering non-traditional employment, such as working in munitions factories, received better pay and welfare benefits than those in ‘traditional’ women’s areas such as clothing, textiles and food processing. But government Manpower Regulations were inflexible and did not allow women to change from traditional jobs to the better paid war work. Even women doing ‘men’s work’ received only 60% to 90% of men’s wages.

Factories were frequently unhygienic, ill-ventilated, poorly lit places which lacked such basic facilities as canteens or separate women’s toilets. Often management refused to provide protective or properly sized clothing, such as women wearing men’s gloves which increased their risk of getting caught in machinery. Women did protest at times about such conditions but found little support from unions. For instance, only when agitation gained women at the Reliance Manufacturing Company publicity, did the union agree to call in the factories’ inspector who effected improvements.

Women also became aware for the first time that the product of their labour was important to the economy and was vital for the lives of the fighting men. According to a West Australian munitions worker:

You’ve got to put out a perfect bullet for the simple reason that they used them in the aeroplanes, and if it jams their guns, well it could kill all the men. After all, if you’ve got a jammed gun you lose your aeroplane. But more importantly, you lose somebody’s brother, husband or son. (Gail Reekie, 1996)

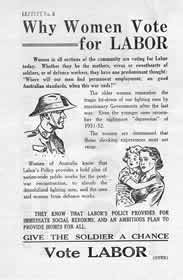

‘Why women vote for Labor’ poster

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of the Australian Labor Party WA Branch. Miscellaneous correspondence ALP State Executive, Federal Elections 1943, How to Vote. JCPML00365/39. Original held by Battye Library: 1719A/17.6

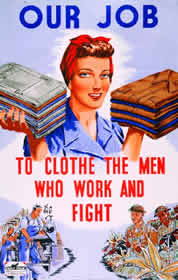

‘Our job to clothe the men who work and fight’ poster, 1943. Artist unknown.

Courtesy Australian War Memorial: Accession No. ARTV01064

Independence

The independence that young, single women gained through employment was often frowned upon as placing them beyond the accepted control of parents and husbands. Rather than going straight from the parental home to that of their husband, single women could afford to ‘flat’ with girlfriends.

A voice for women

From 1941 women’s organizations lobbied to have female representatives on government committees dealing with housing, rationing and other areas of civilian life. These requests met with little success. Mary Ryan, a nurse and member of the Country Women’s Association, was appointed to the Commonwealth Housing Commission in 1943 and Kathleen Best, a servicewoman, became Assistant Director of Women’s Re-establishment in 1944. In 1943 the Australian Women’s Conference for Victory in War and Victory in Peace, the largest women’s conference held in Australia, gave delegates a forum in which to articulate their demands for equal status and equal opportunity and for improvements in health, education and child care. On the political scene, the first Federal female politicians were elected in 1943 with Enid Lyons as a Member of the House of Representatives and Dorothy Tangney as a Senator representing WA.

Happy Homemaker

Despite Mary Ryan’s claims that: ‘Women will demand a new deal – servicewomen and war workers will not willingly return to the humdrum monotonous existence within the four walls of their home’ (Carolyn Allport, 1981) the expectation at the end of the war was for married women to voluntarily resign, leaving positions available for men.

As women lamented (Gail Reekie, 1996):

Most of the women were wanting to get married, and in those days when you married you stayed home and had your family, because it was the thing to do. And besides, the jobs weren’t available. If you married you were expected to leave your job…You didn’t have a choice.

We had to have a job and they took us on again, so well and good. But it was very difficult to settle down to the routine of office work…It was back to what we were before, nothing had changed, and yet we had changed so much.

(A munitions worker)

(A single servicewoman)

The modern homemaker c. 1950s.

Courtesy Northern Territory Library: PH0141/0332 Lorman Collection

The government’s plan for ‘full employment’ focused on men. For women, the emphasis was on modernising homes to take the drudgery out of housework and to provide facilities within the new housing settlements that were mushrooming in the suburbs.

Postwar reconstruction provided possibilities for improvement to the lives of Australian women. Prior to World War II, the Depression had meant unending hardship and struggle for the majority of Australian families. This new era offered secure employment for the family breadwinner, better social security support through child endowment, widows’ pensions, unemployment and sickness benefits and the promise of better housing, including the acquisition of household appliances to reduce the drudgery of women’s housework. Reconstruction planning also offered educated women opportunities to improve women’s status in society, increase the female wage rate and participate more actively in public life.

ELSIE AND ELEANOR

Elsie Curtin and Eleanor Roosevelt fulfilled their important roles through two very different lifestyles: one, the stay-at-home wife providing support behind the scenes and the other, working hard in the public arena to help her husband. They first met in 1943 when Eleanor came to Australia and they renewed their acquaintance in 1944 when the Curtins visited America. Years later when both women were widowed, they continued to correspond.

Stand by your man

As a young girl Elsie grew up reading and discussing political issues with her father and joined the Social Democratic Foundation when she was just 17. Her lifelong interest in politics and social issues, as well as her good nature and lively sense of humour, made her an ideal partner for John Curtin.

Elsie Curtin – one of her favourites photos

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of the Curtin family. Mrs Elsie Curtin nee Needham. (Date of sitting) 14/7/1942. JCPML00376/15

Elsie and John met in 1912 when he came to Tasmania to sort out union problems and speak on behalf of her father who was standing as a political candidate. Elsie took a close interest in John’s political activities, encouraging him to run for political office. She provided advice and support and acted as a sounding board for many of his ideas and speeches.

Elsie never sought the limelight, preferring to run the household, help with John’s electoral work and participate in the local Labor Women’s Organisation. However, as prime minister’s wife she was expected to undertake various public duties. She launched ships, entertained at the Lodge and gave occasional press conferences. Elsie believed strongly that women had a duty to be politically aware and at a press conference given in America, she revealed her hopes that women would have a larger share of public life after the war and might even be consulted at the peace table.

Throughout their marriage John Curtin derived strength and stability from Elsie’s unwavering support. For the last two months of his life she was in constant attendance as his devoted companion. After his death Elsie expanded her interests in community affairs. In 1955 she became a Justice of the Peace, sitting in the Married Women’s Court for several years. She was granted life memberships of the Royal Association of Justices, the Women’s Justices Association of WA, the Perth branch of the Association of Civilian Widows and the Fremantle Labor Women’s Organisation. In 1970 she was appointed Commander of the British Empire (CBE) for her services to the community and the encouragement she gave her husband. Elsie Curtin died in 1975.

Eleanor Roosevelt in Australia, 1943

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of the Curtin family. Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt on a visit to Australia, September 1943. JCPML00376/88

First Lady

An independent and strong-willed young girl, Eleanor Roosevelt married her cousin Franklin when she was just 21. Her leadership and administrative skills emerged during World War I when she was a tireless fundraiser and volunteer with the Red Cross.

In 1919, after women won the right to vote, Eleanor became involved with her husband’s political campaigning and developed a serious interest in politics herself, seeing it as a means to ‘right wrongs…to be of use.’ After Franklin contracted polio, Eleanor took a more influential role and she became an inspired speaker. She achieved national recognition in her own right and some of the causes she championed included:

- a 48 hour working week

- anti-child labour laws

- equal education for girls

- rights for workers.

As well as being a wife and mother, Eleanor took on the roles of publisher, editor, columnist, radio personality, debater, business woman, teacher and political activist. As First Lady, Eleanor championed women’s causes and spoke out on subjects of vital importance to them. She also carved out a position as the eyes, ears and legs of the wheel-chair bound President, travelling across America to keep in touch with people, visiting coal mines and construction sites, farms and factories.

In August 1943 she undertook a tour of the South West Pacific to visit American soldiers, as well as coming to Australia to meet Prime Minister John Curtin and his wife. Shortly after the President’s death in April 1945 she spoke at the San Francisco Conference to charter the United Nations. From 1946 she chaired the UN Commission of Human Rights. During the 1950s she travelled widely as an honorary ‘Ambassador of the World’. Under J F Kennedy’s administration Eleanor served on the Advisory Council of the Peace Corps and chaired the Commission on the Status of Women until ill health forced her to retire in 1962, shortly before her death.