After a turbulent 1916, with all its debilitating anti-war and anti-conscription battles, Curtin's comrades sought a less frantic political climate in which he might recuperate. They chose Western Australia.

Present day journalists might write that there was a move to parachute Curtin into the vacant editorship of the Westralian Worker. This seemed to have failed when he was ranked only second on the short list.

However, the first choice of the paper's publisher, the People's Printing and Publishing Co (Motto: A drop of ink will make millions think) rejected the job offer.

Curtin arrived in WA in February 1917, after a rousing farewell from the Victorian socialists and a confused welcome in WA. The Sunday Times called him Jim Curtin.

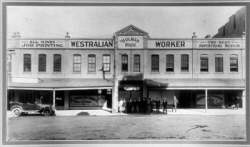

The Australian Workers' Union building in Perth housed the Westralian Worker offices. Records of the Australian Labor Party WA Branch. Westralian Worker Building, 1920. JCPML00379/1.

He still had limited hands-on experience: he had never worked on an 'ordinary' newspaper with multiple deadlines. He came to a conservative state whose journalists provided some of its few bohemian elements, like Edwin Greenslade 'Dryblower' Murphy who often wrote on brown paper bags and arrived at the Sunday Times office, next door to the Worker, in blue-striped pyjamas.

The paper's conservatism had become a problem for the Australian Labor Party which had just split over conscription. The previous editor, John Hilton, was a supporter of the Labor renegade prime minister, W M Hughes, and had run articles praising him and supporting conscription.

Curtin's task as he moved into the editor's office, defined by frosted glass partitions on the first floor of an Australian Workers Union building at 38 Stirling Street, Perth, was to bring the paper into line with party policy on both of these topics.

He began it with gusto.

In his first editorial he attacked Hughes and his new coalition cabinet in the strongest terms.

He condemned Hughes as a traitor to his class and a spokesman for profiteers and 'food pirates' (along with 'food brigands' one of Curtin's favourite phrases). The workers would suffer.

Hughes

Goes to the Tory Camp

----------

Cabinet

of Six Liberals Governs

Australia

Already it is announced that substantial modifications are to be made in respect to taxation. Wealth is not now to be called on to do its share in meeting the national necessities. Repatriation schemes go to the four winds of heaven and the bowed back of Labor can now expect to have the stinging lash of unemployment and sweated industry applied unrelentingly.

Westralian Worker 23 February 1917

Curtin had by now gained control over his flow of words but his style remained decidedly rabble-rousing. Such attacks continued throughout the last two years of the war, rising to a crescendo during the conscription campaign of 1917.

As the war drew to a close Curtin's editorials stressed the need for peace by negotiation, emphasising the dangers of a punitive attitude towards Germany.

At the same time Curtin launched fiery attacks on imperialism and the capitalist system. Workers should overthrow it. There were 23 such editorials in 1919; 31 in 1920, 42 in 1921; and 18 in the first half of 1922.

The best examination of Curtin's editorials is still Dianne Sholl's 1975 thesis 'John Curtin at the Westralian Worker 1917-1928'. This extract covers the peace negotiations.

Extract

from thesis

'John Curtin at the Westralian

Worker 1917-1928'

-------

By Dianne Sholl,

1975

Curtin was inevitably bitterly disappointed with the Peace Conference which eventually gathered at Versailles. He felt it consisted of delegates who did not represent popular opinion but were the agents of imperialist interests more concerned with dividing up territory than with promoting peace. He was extremely critical of the peace treaty which imposed very harsh terms on Germany, and saw the League of Nationals created by the Conference as a reactionary, undemocratic body composed of delegates who had not been popularly elected but merely appointed by governments which meant to use the League to serve the interests of property.

Because of travel and illness not all editorials would have been written by Curtin. But he must have approved of them. In his choice of editorial target Curtin was at odds with Labor politicians, who were at pains to emphasise their lack of connection with Bolshevism.

Curtin liked to put the politicians in their place, as in his editorial of 16 March 1917.

John

Curtin aged 34

1919. Records of the Curtin family. JCPML00376/136/1.

Thou

Shalt Not be Divided.

--------

Where the

Working-Class Party

Stands.

------

The men and women of Labor are not the mere camp-followers of a group of politicians. They have not worked and struggled through the years that the materials may exist for a few ambitious leaders to participate in the game of European statecraft. The organisation of Labor is more important and more necessary than any group of men, however long they may have been in Parliament, and howsoever brilliant may be their intellectual equipment.

***

We can do without them, but they cannot do without us.

Westralian Worker 16 March 1917

There were also comments on strikes as in Curtin's editorial 'The Burden of Labor' of 8 October 1920.

The

Burden of Labor

------

When the day comes that there are no strikes and revolts, no virile protest against the barbarity and injustice of a mad economic form of life, then shall we lose all hope for the progress and freedom of mankind, nay, more, we shall despair even of the survival of the race itself.

Westralian Worker 8 October 1920

From mid 1922 onwards, the Marxist slant had gone. The workers had missed their chance: revolution in Europe had been vigorously suppressed.

Curtin acknowledged there would be no social revolution in his editorial of 2 June 1922.

A

Word to the Labor Congress

--------

Just when Labor should have been most militant, most assertive, and most aggressive, it was most docile and most willing to passively await for the new world of the morrow.

Westralian Worker 2 June 1922