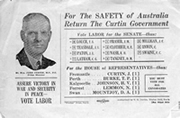

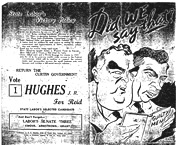

JCPML. Records of Morris Hughes. Did We Say That? 1943 Federal Election pamphlet, NSW State Labor Party. JCPML00278/1

It is measure of the demands placed on a wartime prime minister. especially one representing a Western Australian seat, that during the whole of the second half of 1943 the only time Curtin spent in Perth was firstly, while campaigning during the last week of the election campaign followed by a few days rest and recuperation in Cottesloe where it was written that he

potters around the garden of his modest brick villa . . . spends many hours in the pleasant booklined sitting room reading . . . [but] with a daily visit from his private secretary . . . scan cable messages keeping him in touch with the latest war developments and signs essential papers as Minister for Defence. 70

and secondly, after leaving Melbourne for Perth in the evening of December 26 having just spent his third successive Christmas away from home.

The decision to reverse his 1940 election strategy when he delivered the policy speech from Perth and spent the early days of the campaign in Perth can be attributed in part to the different demands on a prime minister as compared with an opposition leader but also, as David Day has suggested, that

In the 1940 election campaign Curtin had ignored his own electorate so that he could concentrate on boosting the vote in the eastern States. This time, after beginning in Brisbane, he would travel south by train to the other capitals, speaking at meetings as he went before landing in Perth where he would spend the final week of the campaign. He would take no chances with Fremantle. 71

Certainly, delivering his policy speech on 26 July from Canberra served to emphasise Curtin’s ‘position as a national leader’. 72 His itinerary then took him to Brisbane (from 28 July); Sydney and Eden-Monaro/Goulburn (from 31 July); Victoria commencing with Ballarat from 4 August; Adelaide and South Australia from 10 August; after which, as already indicated, on Sunday 15 August he made what was only his second ever plane journey in a Lancaster bomber to Perth. 73 While in the West his appearances were largely focussed on the Fremantle electorate including the much publicized national broadcast from Fremantle Town Hall on 18 August in which, as already indicated, he asserted both that ‘the Labour government would not, during the war, socialise any industry’ 74 and that ‘the Labor party had no affiliation with the Communist party’. 75

In his final statement before polling day he described the contest as ‘the most momentous election in the history of Australia. 76 As the results came in on the Saturday night his personal secretary who was with him in the hotel room on which the results were displayed suggested that ‘ . . . within a short time it was all over. He’d won an outstanding victory’ 77 both at the national level and in Fremantle where his majority had increased from just over 600 votes to more than 20,000.