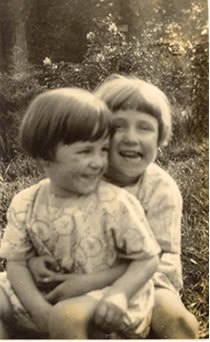

Madelaine and Elizabeth Knight

Photograph courtesy

of Mrs Madelaine Blackmore

... "overdone" displays of Christianity ...

Childhood

In their backgrounds, beliefs and behaviours, Elizabeth Jolley's parents Charles Wilfrid Knight (called Wilfrid [1890-1977]) and Margarethe Johanna Carolina Fehr Knight (called Margarete in England [1896-1978]) were more contradictory than complementary. His family descended from dour Methodist labourers-cum-dairy farmers in Winterslow, Somerset, while she said hers descended from seventeenth-century Swiss aristocrats. By the time Jolley was born, her paternal grandfather was a purveyor of watered-down milk in Wells where he was also a lay Methodist evangelist, and his wife was a school mistress. Despite Margarethe Knight's claim that her father was a judge and a general in Vienna, Walter Rudolph Arnold Fehr (1862-1928) was a station worker for the Austrian state railroad; her mother Anna Margarethe Kramer or Krammer (1874-1901) died of tuberculosis when she was twenty-six and her daughter Margarethe five years old.

Wilfrid was a school science master in the greater Birmingham area; Margarete Fehr Knight, a kindergarten teacher in Vienna, taught German in night school at Aston Technical College and later tutored from home. They were married in the Methodist Church in Vienna on 13 July 1922 when Wilfrid went there with a post-war Quaker relief mission (according to one story) or to ask Sigmund Freud to help him become a psychologist (according to another). Elizabeth Jolley was born as Monica Elizabeth Knight at The Norlands Maternity and Surgical Nursing Home in Gravelly Hill, Erdington (near Birmingham), on 4 June 1923, and her sister Madelaine Winifred was born at The Norlands on 20 August 1924. Wilfrid and Margarete nicknamed Madelaine "Baba," calling Monica "Bunty" (the husband's spelling) or "Bunti" (the wife's).

The Knights' differences were more than just orthographical. For example, Wilfrid Knight was deeply religious, a Methodist lay evangelist when he was a teenager. In 1917, while imprisoned as a conscientious objector against World War 1, the example of a Quaker CO hunger-striker persuaded him to identify with Quaker pacifism. (On his release, his father threw him out of the house with a shilling for good riddance for having shamed the family by being imprisoned.) Then, in 1938, he dramatically re-embraced Methodism, subsequently studying formally to qualify as a lay preacher. Quick to anger until that point, he was placatory after that. Margarete Knight, rebellious after a convent-school education, rejected Roman Catholicism and was either an agnostic or an atheist who was irritated by her husband's "overdone" displays of Christianity. Not a pacifist, she at first had an open mind about Hitler, enjoying the radio broadcast of his speech after the fall of Warsaw in October 1939; but she later became a champion of Churchill, crying throughout his funeral which she watched on television in January 1965. He could become rigid and white-faced with anger, while she was prone to red-faced outbursts and hurtful recriminations.

Margarete Knight appeared to have an aversion to women, particularly women in her own home, perhaps derived from her father's remarrying twice after her mother's death, the second stepmother being a strict disciplinarian who sent her to the Klosterchule. Margarete Knight would rant at her daughters and occasionally slap them; she humiliated Madelaine by saying she had not wanted a second child, and certainly not a daughter; and she treated her brother Walter Fehr's fifteen-year-old niece rudely when she came to visit from Vienna. In those circumstances, her daughter Monica also became a placator who would try to mediate between and among family and friends.

Men were attracted to Margarete Knight. In particular, "The Friend of the Family" was twelve-year-older Kenneth Berrington, a well-to-do bachelor barrister ("Mr Berrington" p. 32, Jolley's italics) Margarete Knight met in her German class at Aston Tech. Since he lived nearby, she invited him to come for private lessons at their home (or sometimes at his) on Thursday afternoons. He also visited every Sunday for the noonday meal, took her and Madelaine to Europe for six weeks during the summer of 1936, and Monica and her to the continent two years later. And he left Margarete Knight £63,000 when he died in 1956.

Sometimes it seemed what Wilfrid and Margarete Knight had most in common was that they did not smoke or drink or own/drive an automobile, were bilingual in English and German, between them knew several other languages, and kept up with politics and current affairs. He was liberal, she conservative; she was a royalist, he a republican; he preached tolerance, she spoke badly of Jews and black Africans, although in practice she was generous and welcoming to many Jewish refugees. She loved the works of Beethoven, Mozart, and Schubert, while he was indifferent to music; she loved Goethe and other German poets, whereas he was more interested in science and in psychology with a Christian bias. Their knowledge of politics and current affairs meant that they never lacked for something to quarrel about.

The tension in the household was relieved by visits from Knight relatives, like the grandfather's cousin, nervous Aunt Dorothy, the grandmother's half-sister, zany Anti Mote (Aunty Maud), and Wilfrid's sister, spoiled and selfish Aunty Daisy. The household was also enriched by a number of pseudo-relatives, most of them Wilfrid Knight's fellow teachers or their spouses and children. Kindly men and women who were well educated and principled, with varied interests and intriguing practices, they were conscientious objectors, Quakers, agnostics, Methodists, atheists, Catholics, a nudist, three men who rode motorcycles (including Wilfrid Knight), a man seeing a psychiatrist (the nudist), and an older man, Dr Otto Stapf (1857-1933), the Austrian-born Keeper of the Herbarium at Kew Gardens. His wife, honorary "Aunt Martha," was another "peculiar" included among Jolley's said-to-be-mad women. Access to this virtual extended family allowed the Knight girls to escape the hothouse atmosphere at home and provided Jolley with some characters and character types for her fiction.

Because of his several years in jail, Wilfrid Knight said, he always

felt unworthy of any house they occupied. After initially boarding in

the Birmingham area, for a few years in the late 1920s they lived in "Flowermead,"

Margarete Knight's dream home; then they moved twice, following his teaching

jobs, before finally settling in Wells Road, Wolverhampton, in the early

1930s, first at number 63 and then at number 62. Perhaps because of his

daughters' brief spells in regular schools along the way, and surely as

a result of his own experiences as a child in Wells and as a school teacher

in the Midlands, Wilfrid Knight believed that school ruined a child's

innocence. Thus he gained approval for home schooling, a regime that quickly

petered out because Margarete Knight did not have the time, inclination,

or skills to teach all of its subjects - and because she drove away the

variety of au pair girls who came from the continent to assist with the

great experiment. Besides, Monica and Madelaine opposed it too, for they

were bullied by other children in the street for not having to go to school

and taunted because they spoke German in the household. When Monica began

to stand up to her mother, answering back and slapping when slapped, Wilfrid

Knight relented and arranged for her to attend the Quaker Sibford School

near the Cotswolds with a bursary from Quaker philanthropist Lucy Sturge.

Elizabeth and Madelaine Knight

Photograph courtesy

of Mrs Madelaine Blackmore

.... conscientious objectors, Quakers, agnostics,

Methodists, atheists, Catholics, a nudist, three men who rode motorcycles...