|

Between Life and Economics - 'A dissenting case'Tom Fitzgerald delivered the 1990 Boyer Lectures Between Life and Economics. For most of the ‘talks’ (as he called them) he expounds ‘a dissenting case…against the prevailing climate of opinion among the policy-makers’ in economics.

Lecture 1: Early perspectives on lifeBy way of introducing himself he devotes the first talk to ‘a few impressions of a general kind about the world and about Australia that have stayed with me from early days’. The first impression was ‘a piece of information from Charles Darwin that gave me the biggest surprise of my life and sent me looking for unattainable explanations’. This information was the ‘puzzling case’ of the life cycle of barnacles, about which Darwin noted that the mature barnacles ‘may be considered as either more highly or more lowly organised than they were in the larval condition’. From the second larval (embryonic) stage to the adult stage, the barnacle swaps six pairs of beautifully constructed swimming legs for relatively crude prehensile organs, a pair of magnificent compound eyes for a single, minute, simple eye-spot, extremely complex antennae for no antennae. The embryonic barnacle has a closed and imperfect mouth and cannot feed; the adult has a well-constructed mouth.

He notes another ‘cause for wonderment’ was that ‘we are living in a very early, indeed primitive, stage of the development’ of human beings. Up to five thousand generations have preceded us, but given that the solar system is expected to survive another few billion years, a hundred million generations could follow us: ‘The future of our race is much more mysterious than its past. None of our scientists can tell us what the far-off human strangers will be like.’ He used to wonder what relationship these ‘speculative immensities’ had to Australia as it was then and as it will be in the future when ‘the margin of our newness by comparison with countries in the Northern Hemisphere would become infinitesimal’. In the context of Australia’s relationship with the Old World, he was captivated by Chaucer.

But he saw complications, prompted by the poetry an Australian, WJ Turner, who had moved to London and was praised and anthologised by WB Yeats. He quotes in full one of Turner’s poems, ‘Hymn to her unknown’, and imagines that it could not have been written like it was, or written at all, if Turner had stayed in Melbourne.

On Fitzgerald's return to Australia after serving in Europe during World War II, he and his fellow air crew experienced an unexpected, hostile reception from ground staff, with the air force vans that collected them from the wharf having ‘large signs scrawled on their sides saying JAP DODGERS RETURN’.

The diarist wrote of the last thirty or so minutes of Flight Lieutenant Newton’s life and describes him as resigned and calm before he is beheaded by a single blow of a samurai sword: ‘He is a very brave man indeed’.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

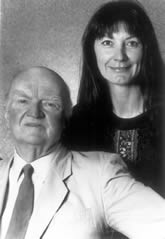

Tom Fitzgerald and Robyn Ravlich, producer of the Boyer Lectures, 1990 John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. Records of the

Fitzgerald family. Tom Fitzgerald and Robyn Ravlich (producer of Boyer

Lectures); September 1990. JCPML00720/64

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lectures 2 to 6: EconomicsIn the following five talks, and in the postscript to the second edition of the book, Fitzgerald presents his dissenting case against the prevailing economic orthodoxy. He contrasts the approach of many of the most eminent economists, who acknowledge ‘increased uncertainty and the provisional nature of conclusions arrived at after the greatest care’, with that of the loud-mouthed, doctrinaire free-marketeers who have abducted Adam Smith and perverted his ideas. He quotes Smith’s criticism of the ‘pernicious effects’ of high profits, and his comment on the greed which is ‘the vile maxim of the masters of mankind’. Fitzgerald notes other instances of Smith’s writings that would confute his abductors: opposition to a consumption tax on food; support for progressive tax rates; distress at the effect routine factory work had on workers, which led him to demand government intervention. Fitzgerald agrees with the eminent economists’ belief in the importance of revising theories based on experience and testing.

He devotes one talk to a case study of Japan, whose economic success up to 1990 was based on widespread government intervention and protection ‘in conscious rejection of Western textbook precepts’ which the Japanese see as deficient in their inability to recognise cases of what they call ‘market failure’. Fitzgerald writes that he wants to ‘break the absurd taboo that exists on the discussion of financial deregulation as a significant contributor’ to the economic problems of the time. In his analysis of the failure of deregulation, Fitzgerald emphasises the importance of the distinction between the tradeable and non-tradeable sectors of the economy, the effects of a large deficit in the balance of payments, the overvalued exchange rate, and the money supply. He is critical of the dominant, unchallenged Treasury view of the world when Paul Keating was Treasurer. Fitzgerald quotes comments by Frank Anstey (when an MP) and his young protégé John Curtin (when a trade union official) in which they acknowledge the responsibility their privileged positions entail, and the inner conflict, as Curtin wrote, of ‘receiving more than you justly earn’. Fitzgerald traces the development of Curtin's 'hard, independent thinking on economic subjects' as a contrast to the then Labor government's ineffectiveness 'in preserving commonsense economic principles'. In closing, Fitzgerald returns to some themes from the first talk.

Footnotes1

- 8. Fitzgerald, T, 1990, Between life and economics, Crows Nest,

N.S.W, Australian Broadcasting Corporation |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||